Environment: Sustainable Farming Incentive and Carbon Outlook

Thursday, 29 July 2021

Climate change has made the leap from political rhetoric into policy reality. It’s an issue that will increasingly manifest itself in national and international policy decisions, as well as supply chain standards. At the same time, there is an industry commitment to a path towards Net Zero emissions.

By Jon Foot

Farm businesses will have to balance environmental sustainability with the impact on production systems and financial viability. Farmers and growers will need to navigate a new and uncertain policy landscape, which may reward some practices (via future agricultural policy) and penalise others. This article aims to explain how farming carbon may become central to every farm business.

A significant driver of change will be climate change with the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and the use of natural systems to lock up carbon to achieve net zero carbon emissions. It should be remembered that neither NFU Net Zero Goals or government targets expect all farms or even all sectors to achieve net zero.

To mis-quote George Orwell’s Animal Farm “all farms are equal, but some are more equal than others”, and this means farmers and growers may group together to optimise the ability for others to carry the load in some areas, whilst others may do less.

All the signs are that farmers and growers will have to measure their carbon stocks, emissions and demonstrate how the products they are producing can be done so with less carbon.

So why should farmers and growers do this? Where is the money to be made?

These are good questions, so let’s start with the big picture and then bring it back to the farm level.

The majority of environmental and sustainability changes are likely to result from policy and regulation to mitigate climate change. The Agriculture Act 2020, Environmental Act 2021, and the Streamlined Energy and Carbon Reporting (SECR) 2019 are key examples of this.

In the supply chain, food processors and retailers are being driven by legislation to measure and report their emissions, including the carbon in the products and services they buy (also called Scope 3 emissions). The increasing demands of consumers of both product choice, shifting diets and climate change concerns will also drive this agenda and accelerate change.

The broader challenge for agriculture and society as a whole; is how do we produce low carbon/sustainable, safe, affordable and secure food supplies in a world where there will be greater demand for food, and in particular good quality protein, while at the same time increasingly deliver public goods and services?

AHDB has a clear role in assisting the agricultural sector to understand and minimise its carbon emissions, particularly in the livestock sectors. Carbon management is good for business - lower carbon footprints are often associated with higher efficiency, above average yields and better margins.

We are supporting our levy payers on this journey with a three-step approach.

We have recently completed a project delivering carbon audits on 50 of our Farm Excellence farms. The audit process identifies and quantifies the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with all farm inputs and activities, creating a baseline from which farm businesses can monitor change as they take action to reduce emissions.

The highest emissions and mitigation priorities will be different for each sector, but generally fall into three main categories: Feed, Fertiliser and Fuel (the 3F’s). Crops’ main source of emissions is the use of fertilisers. Methane production from ruminant livestock is impacted by the efficient use of feed and forage. And although fuel plays a smaller part in these systems, it can be important in intensive livestock and crop storage systems. Data can quickly and easily be obtained from supplier invoices. Optimising the 3F’s will save money, increase your margins, without reducing your outputs. They will also deliver reduced carbon emissions and in many cases wider environmental benefits at the same time.

We will continue to expand the number of our strategic and monitor farms that are using carbon tools to measure their carbon footprint. As we build the network we can see what works for reducing carbon and increasing farm incomes. This is a significant step for us in helping farmers address this increasingly important topic. We will roll out a wider campaign to raise awareness of how farmers can take action using the carbon tools that are available on the market, and will recommend:

- Start using a carbon measurement tool

- Don’t worry whether it’s 100% accurate

- Choose one that works for you, or your customers

- Use the same tool every year, to help with consistency

- Choose 1-2 areas to improve and that make you money

- Keep measuring and improving, and adapt the plan where it makes sense to

- Keep a record of progress and actions for reporting to customers and celebrate your success

This step is a few years away for most land managers and should only be done with expert advice. For many in the industry, payments from the Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) (formerly ELMs) will provide opportunities to sequester or lock up carbon for the medium to the long-term using nature-based solutions (i.e. planting trees, restoring peatlands, restoring hedges, building soil carbon). The government has set out plans to phase out direct payments as it introduces a new SFI scheme.

Basic payments to farmers in England will be halved by 2024 and phased out completely by 2028. In England, there will be 3 new schemes that will reward environmental land management:

- Sustainable Farming Incentive

- Local Nature Recovery

- Landscape Recovery

These schemes are intended to support the rural economy while achieving the goals of the government’s 25 Year Environment Plan and net zero emissions by 2050.

Through these schemes, farmers and other land managers may enter into agreements to be paid for delivering the following:

- Clean and plentiful water

- Clean air

- Thriving plants and wildlife

- Protection from environmental hazards

- Reduction of and adaptation to climate change

- Beauty, heritage and engagement with the environment.

For SFI in England and similar schemes in Wales and Scotland, farmers will be required to demonstrate that they are delivering the outcomes required by the scheme in order to continue to receive the payments.

The scheme is made up from a set of standards. Each standard is based on a feature like hedgerows or grassland, and contains a group of actions you need to do. As a land manager, you can choose the standards you want to do, and where on your land to apply them. You will then be paid for doing the actions within the standards you choose.

View the payments for the SFI pilot phase and an example for grasslands is shown in Table 1

Table 1: SFI Payments for grasslands, that can deliver biodiversity and carbon savings

Introductory level (£27 per hectare) |

Intermediate level (£62 per hectare) All actions in the introductory level plus |

Advanced level (£97 per hectare) All actions in the introductory and intermediate levels plus |

|

Increase above and below ground biodiversity by grazing to retain a minimum sward height |

Increase biodiversity and provide habitat for breeding birds by altering the timing of your silage cuts |

Increase biodiversity and habitats for wildlife by managing grazing or cutting to provide a higher sward height over a larger area |

|

Increase habitats for insects and small mammals by leaving uncut margins to produce flowers and seeds |

Increase habitat for farm and aquatic wildlife through rotational ditch management |

Improve soil structure and biology and provide increased pollinator resource with legume and herb-rich swards |

|

Protect your areas of historic interest by maintaining permanent grassland cover on them |

Improve nutrient use efficiency and reduce losses to the environment with a nutrient budget |

Increase the food available for birds in winter by leaving some ryegrass to bear seed |

|

Protect soils and reduce loses to the environment by following a nutrient management plan |

Use slurry more efficiently by testing content, managing application rates and using low emission technologies |

Better target your nutrient application by carrying out soil mapping |

|

Provide more habitats for wildlife by taking small areas out of cutting and grazing management |

Improve your soil structure and biology, provide pollinator resource and reduce fertiliser application, with clover and legumes |

Use efficient precision application equipment for fertilisers and organic manures |

|

Additional action |

As in introductory level |

As in introductory level |

Beyond the more basic payments in the pilot phase, is the Local Nature Recovery scheme, which will pay for actions that support local nature recovery and meet local environmental priorities. The scheme will encourage collaboration between farmers, helping them work together to improve their local environment. This scheme will begin piloting in 2022 and launch in 2024.

This may also give some opportunities for farmers to collaborate to deliver both nature recovery and carbon sequestration opportunities. It is likely that in such circumstances, the SFI will pay for the biodiversity recovery aspects, and private agreements may pay for carbon sequestration opportunities. When developing these schemes, farmers may wish to consider the creation of a limited company or other vehicle to ring-fence the opportunities and liabilities.

The Landscape Recovery scheme will support landscape and ecosystem recovery through long-term projects, such as:

- Restoring wilder landscapes in places where it’s appropriate

- Large-scale tree planting

- Peatland and salt marsh restoration

The scheme will begin piloting around 10 projects in 2022 and be fully rolled out from 2024. For most farmers and land managers these opportunities may build on existing long-term projects, and there are considerable opportunities to be rewarded for locking in extensive land use change that enhances biodiversity and carbon offsets.

Some businesses, both inside and outside of agriculture, have greater capacity to reduce their emissions of greenhouse gasses than others. This difference in reduction abilities means that those that can make significant emissions reductions have the opportunity to sell those savings to others. Meaning those who buy carbon savings are in a better position to achieve their own emissions targets. This exchange might be through participation in a formal trading scheme managed by a national government, or on an entirely voluntary basis.

Compulsory trading schemes: to link or not to link?

The compulsory carbon trading schemes do not currently apply to UK agriculture, but we’ll explore in this section why they might be of interest to us in the future.

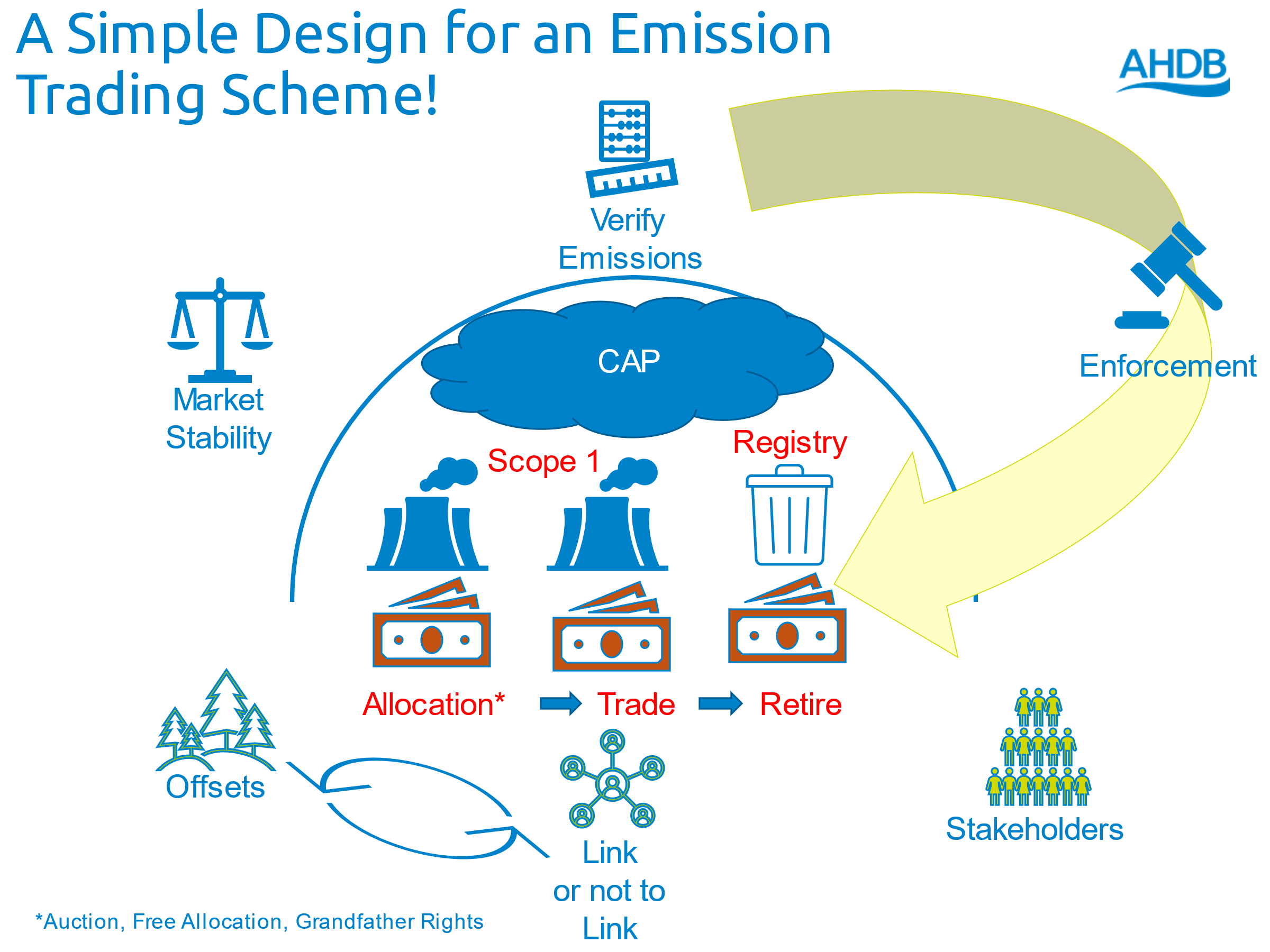

Businesses may be part of a ‘cap and trade’ scheme. The total amount of greenhouse gases that may be emitted each year is determined at a governmental level according to agreed national targets. This is the ‘cap’ and it reduces over time until a final annual emissions target is met, such as the UK’s net zero by 2050.

For example, the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) operates in all EU countries, limits emissions from around 10,000 direct and associated activities in the power sector and manufacturing industry, as well as airlines operating between these countries. Participation for these is compulsory, and the scheme covers around 40% of the EU's greenhouse gas emissions. A UK Emissions Trading Scheme (UK ETS) replaced the UK’s participation in the EU ETS on 1 January 2021. The UK ETS will apply to energy intensive industries, the power generation sector and aviation.

Similar schemes exist elsewhere, including in parts of the US, New Zealand and China but they are not yet linked. The Paris Agreement, adopted by 197 countries serves as an example of how international emissions markets could be linked in the future.

In trading schemes such as this, businesses have their emissions measured, verified and audited. At the end of each compliance period, they must surrender carbon credits equivalent to their emissions in that period. If they don’t, they typically face a fine, as well as mandatory purchase of credits equal to the shortfall. Depending on the scheme, participants may be given some credits for free, or they may buy them in an official auction. They can also trade with other participants on the open market, buying or selling as necessary. Free allocations aim to prevent ‘carbon leakage’ where manufacturers move carbon-intensive industries overseas.

The advantages of an emission trading scheme are that the cap provides certainty for policy makers, and it provides a flexibility for compliance route for the industrial participants. However, creating a market in something with no intrinsic value is very difficult.

Carbon trading scheme such as the UK ETS are not suitable for agriculture, because the monitoring and reporting requirements would be a disproportionate burden for the industry, and the data required to underpin the scheme cannot be directly measured in a timely and transparent way. It is only where the mandatory scheme is linked to voluntary offsetting schemes that there may be some opportunities.

A glut of allowances or loss of confidence has led to a collapse in the price of carbon, and this can result in the scheme delivering no effective emissions reductions. In the early stages the voluntary offset allowances were traded, often at a discounted price, which also deflated carbon prices. In many emission trading schemes the ability to trade voluntary allowances has been significantly curtailed or stopped.

At the end of 2020, the cost of EU allowances was €33.43 (£28.84) per tonne. It has since risen to €56.35 (£48.61), following rising EU and national climate ambitions. The UK ETS allowances are trading at between £44-50 per tonne of CO2 (May 2021), which closely mirrors the prices in the EU, and this linkage is likely to continue. However, the UK market has less liquidity because it is smaller; and so, prices are likely to be more volatile. There are currently no plans to link the mandatory and voluntary carbon schemes in the UK or within the EU.

Voluntary offsetting

Businesses not covered by schemes such as those described above may also wish to reduce the amount of greenhouse gasses they emit on a voluntary basis. They can do this themselves, or by buying credits from others.

Voluntary offsetting: how to take part

There are a lot of schemes promising farmers an income for growing carbon. However, all is not as certain as promised, and the returns come with risks, because there are few recognised standards or schemes here in the UK.

UK landowners are most likely to be familiar with this sort of carbon trading in the form of voluntary offsetting, either through the UK Woodland Carbon Code, or the Peatland Code. With both of these schemes, verified emissions savings can be sold to other businesses seeking to offset their carbon footprint. Project details are held for public view by IHS Markit in the UK Land Carbon Registry. At the moment, carbon savings generated under these schemes would not be saleable into an emissions trading scheme.

Some new schemes are trying to sell carbon credits linked to the idea that soils are a vast carbon sink that remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, helping reverse climate change with farmers being paid for the carbon they store by companies wanting to offset their emissions. However, there are some significant problems with these schemes in that they fail to meet the key principles of:

- The carbon offset must be quantifiable. This requires the organisation wishing to offset their carbon to be able to measure and quantify the amount they need to offset, and for the land manager to be able to demonstrate that the offsets are delivering the benefits contracted for.

- Additionality must be demonstrated and is hard to do (see box below)

- There must be no carbon leakage (see box below)

- The offsets must be permanent.

If the carbon offsets do not meet these requirements, then you should consider other options. Likewise, where the schemes lack an underpinning standard such as the Woodland or Peatland codes, it would be worth seeking further advice before making a commitment. When entering into these schemes, you also need to consider whether there is a long-term income to maintain the offset scheme, rather than a one-off injection of money into your business. Legal advice should be obtained to ensure the scheme is protected by covenants and there are legal protections and indemnities to protect you and your business should the project fail for reasons beyond your control (i.e. drought, vandalism etc.).

Whilst I have highlighted some of the negatives of offsetting, I am very optimistic about the future and the role of offsets for biodiversity and carbon. The AHDB will push for standards that support the development of the voluntary offset market and enable multiple benefits to be stacked for projects that are able to demonstrate that they are delivering across a range of environmental issues. Standards and new guidance are being developed that will help to demystify this complex area. The recently published ‘Oxford Principles’ provide some good principles for how carbon offsetting can contribute towards net-zero.

The offset market will provide levy payers with new income streams and opportunities, for land that may be less suitable for food production. The offsets will be increasingly needed by all sectors of the economy. We should also be promoting the development of offset markets in the short to medium term to provide a quicker road to carbon neutrality, whist investment in technology catches up to drive more direct decarbonisation for sectors where decarbonisation is cost-effective. In the longer-term offsets are going to be required along with nature based solutions to achieve the government’s net zero targets by 2050.

AdditionalityAdditionality is one of the key tests for good quality of carbon offsets. The major concern is that where claims associated with a project are not delivering additionality the purchase of offsets is at best doing nothing to tackle climate change and in most cases, it will still be contributing to making climate change worse, because there is no net reduction of emissions. GHG reductions are additional if they would not have occurred in the absence of a market for offset credits. If the reductions would have happened anyway (i.e. without any prospect for the sale of carbon offset credits), they would not be additional. For agriculture it is often very difficult to assess additionality. |

Carbon leakageCarbon leakage occurs when there is an increase in greenhouse gas emissions from one country with lower standards for quantifying carbon, from the one that has on paper reduced its emissions. This often involves moving production from the UK to other countries. This can make the UK look better, but we’ve just outsourced the problem, so there is no net reduction of emissions, and climate change continues to get worse. |

Topics:

Sectors:

Tags: