Understanding the two types of carbon market

Thursday, 24 November 2022

Carbon markets – the world of trading the emissions and offsets of greenhouse gases – are becoming an increasingly important part of the economy. They are a growing part of the world’s efforts to combat climate change. They also have increasing relevance to farmers and growers, as we have recently discussed, representing an opportunity for an additional income stream.

These carbon markets can be complex, but we are going to break down the basics in this series of articles so you can understand what carbon markets are, how they work, and what you need to know.

One of the first steps in navigating carbon markets is to understand the two broad types of market: the compulsory market, and the voluntary market.

The compulsory market is government-regulated, where companies have a legal limit to their emissions but can buy or sell allowances with other companies – similar to the old milk quotas.

The voluntary market is where companies can choose to offset their emissions by buying credits generated by carbon-sequestering projects.

Both markets work on the basis that 1 carbon credit = 1 tonne of CO2 equivalent.

Of these two, the voluntary market is most relevant to farmers and growers, as there is the potential opportunity to sell carbon credits. However, it is still worth being aware of the compulsory market, as buyers may ask their farmers to reduce emissions as part of the limits set on them by the government.

Both markets are explained below. If you want to know more about why you should care about carbon markets, and what prices carbon credits can fetch, see our previous article.

Compulsory carbon markets

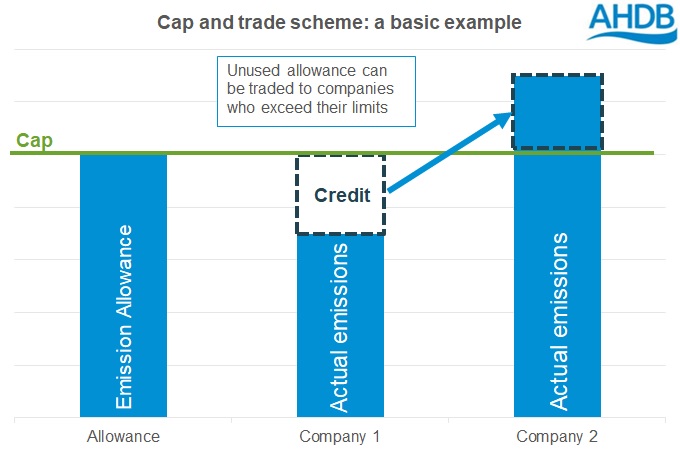

Most compulsory carbon markets work on a “cap-and-trade” system. The government sets a limit of how much greenhouse gases each company can emit – the “cap”. If a company is under their allocation, they can sell their spare allowance to a company that would otherwise exceed their limit – the “trade”. The level can be lowered each year to encourage companies to reduce their emissions.

In the UK, this market is run under the UK Emissions Trading Scheme (UK ETS), which replaces the EU ETS we were previously a part of. This cap-and-trade scheme applies to energy intensive industries, the power generation sector and aviation. Outside this, small emitters are given targets instead of an allowance, and ultra-small emitters only have to monitor their emissions. For those covered by the scheme, businesses have their emissions measured, verified and audited. An allowance for each company is then calculated.

Emissions allowances are held in the UK Emissions Trading Registry. This registry tracks who holds allowances, how they are traded between emitters, and also holds details of verified emissions and allowances surrendered by operators.

The UK ETS does not cover agriculture. It is only where the compulsory scheme is linked to voluntary offsetting schemes that there may be some opportunities for farmers. However, it is good to have a basic understanding of compulsory schemes as they are a significant part of overall carbon markets, and pricing on these markets may influence prices on the voluntary markets.

Want more detail? Read our Head of Environment's Carbon Outlook.

Voluntary carbon markets

In the voluntary markets, participation is optional. Companies choose to buy-in in order to reduce their carbon footprints. The carbon credits they buy can come from several types of environmental projects, either those that “remove” emissions, or those that “avoid” emissions. Removal offsets are generated from projects that pull carbon from the atmosphere, such as planting trees. Avoidance offsets are generated by projects that prevent emissions from being released into the atmosphere, such as stopping an area of forest being cut down.

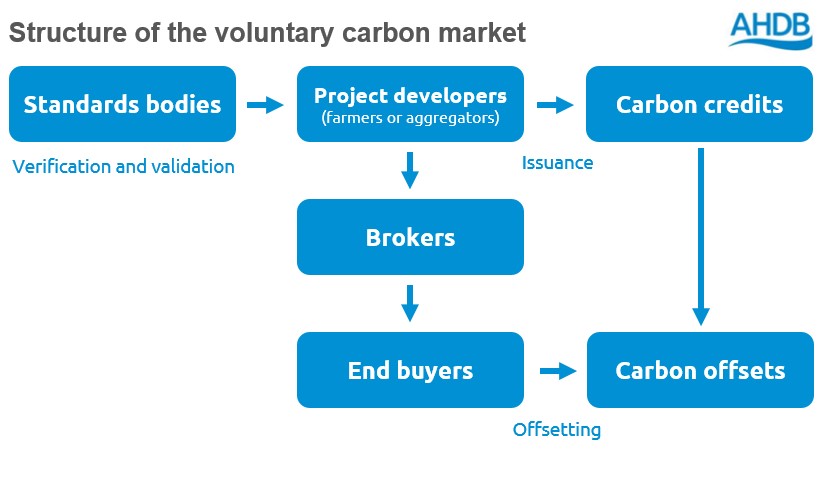

The voluntary carbon market system is not regulated by governments. Instead, to ensure the integrity of the carbon credits being traded, there are independent certification bodies that have defined standards to verify the projects against, providing accreditation. However, with multiple certification bodies out there, this does lead to fragmentation in the market. The perceived quality of different carbon credits can also be variable, which in turn affects both the demand for and the price of those credits.

There are four key participants in the voluntary carbon market:

- Project developers – Coordinate and run carbon credit projects. In agriculture, this could be for a single farm, or the work of several farms could be aggregated together to make a more attractive package.

- Standards bodies – these set the standards for projects, provide certification of carbon credits and hold registries of these projects.

- Brokers – purchase carbon credits and sell them on to end buyers.

- End buyers – Purchase carbon credits to offset their emissions.

What voluntary schemes are available?

There are two UK-specific accredited schemes that landowners can get involved with – the Woodland Carbon Code and the Peatland Code. These schemes are backed by the UK government, and project details are held for public view by IHS Markit in the UK Land Carbon Registry.

There are also multiple international schemes and standards that could be utilised by farmers. There is the potential to generate carbon credits through sequestration – by increasing soil carbon – or by reducing your emissions through improved agricultural practice. These schemes are not government backed, but projects still go through independent verification and accreditation.

What should farmers do now?

Measure your carbon footprint. This is important as the more years of baseline data you can provide, the better. Even if you never end up entering a carbon credits scheme, carbon footprint measuring is becoming increasingly important, and you may find a buyer or policymaker asking for it in the future. There are a range of tools out there, but pick the one that works best for you and keep using it – consistency in method is key to establish improvements over time.

Consider your options. Look at the schemes that are available and consider whether they apply to you. There are many questions to consider, such as: Do they cover your enterprises? Can you meet their requirements? Do I need to own the land, or negotiate with the landowner? Will I make a profit?

Decide whether to act or wait. Sentiment around the markets also indicates that carbon credits are likely to increase in value long-term. In addition, it may not be clear at the moment what requirements may be put on farmers in the future to reduce their own emissions. This may mean that it is better to wait to sell your potential carbon credits. However, others argue that if farmers are already making regenerative changes to their practice, they may be losing out on monetising their results if they wait.

The voluntary carbon markets can be a complex place, with the role of agriculture still developing. AHDB aims to bring clarity to these areas going forwards, to enable farmers to make business decisions in this area.

Want more information? See our previous article on why you should care about carbon markets, and what prices carbon credits can fetch.

We’ll be producing more analysis in the months to come. In the meantime, you can read our Head of Environment's Carbon Outlook.

Do you have a question regarding carbon markets? To get in touch, email carbon.markets@ahdb.org.uk