- Home

- Knowledge library

- Field drainage: The signs of good and bad field drainage

Field drainage: The signs of good and bad field drainage

Surface ponding or saturated topsoil are obvious signs of poor drainage. However, prolonged waterlogging under the surface may not be so easy to spot.

Signs of poor drainage

- Poor crop health or yields

- High surface run-off rates and soil erosion

- Limited field access without rutting or poaching compared with other fields in the area

- The presence of wet-loving plant species, such as common rush and redshank

- Susceptibility to drought due to poor root development and limited rainfall percolation into the soil

Top tip: Overlaying a yield map onto a field drainage map can help identify problem areas.

If drainage problems are widespread across the field, it may be that:

- Soil management is not adequate

- No drains have been installed

- Mole drains need to be renewed

- The outfall may be blocked, especially in flatter fields

- The drainage system requires maintenance or renewal

Know your soils

Examining soils to determine if they are naturally freely or slowly draining, or have damaged structure, should be the first action when drainage problems are suspected.

Without good soil structure, soil drainage will be poor − whether it be by natural drainage or pipes.

It is important to routinely assess soil structure (ideally, in spring or autumn). This can easily be incorporated into scheduled soil sampling activity.

Examine the soil at several points in the field to a depth of:

- At least 600 mm for arable land

- At least 500 mm for grassland

Soil structure

Well-developed structure is evident from the ease of digging and if the soil readily breaks down into small structural units with many vertical fissures.

Soils with poor structure are harder to dig and break down into larger, dense blocks, with poor penetration by water, air and roots.

Where soils are coarsely textured and well structured, the soil may be freely draining enough to support field operations and crop growth without the need for artificial drainage systems.

Learn how to assess soil structure

Soil colour and texture

Greyish-coloured soils and soils with rusty or grey-coloured mottles are signs of poorer drainage.

Usually, the iron compounds in agricultural soils give the horizons a reddish-brown colour.

However, when deprived of oxygen, such as under waterlogged conditions, the compounds change to a grey or bluish colour in one or more characteristic gleyed layers.

Rusty orange-red mottles can also form, where air enters around roots or on the surface of larger pores.

Images © Environment Agency, thinksoils

A – Cultivated topsoil (clay with organic matter)

B – Subsoil (clay, blocky and prismatic structure with mottling characteristic of seasonal waterlogging) – Insert shows medium prism from subsoil (grey but with many rusty mottles as a result of intermittent waterlogging)

C – Soil parent material (grey clay with evidence of waterlogging)

The higher the clay content, the more likely the soil is to be naturally poorly drained.

Consider field drains in:

- Heavy clay soils: these are slowly permeable and, without drainage, can waterlog for long periods − particularly in areas of high rainfall

- Medium-textured soils in high rainfall areas: drainage may be needed to reduce vulnerability to compression, slaking and compaction

- Light-textured soils: these soils are highly permeable, but drainage may be required to provide water table control in low-lying areas

Soil organic matter

There has been a general reduction in organic matter levels in arable soils over the past 70 years. This makes them more susceptible to waterlogging and more in need of drainage.

Learn about soil organic matter

Find out about how to test organic matter

Root development

Deep rooting indicates good structure.

Shallow rooting, with many fine horizontal roots and tap roots that are diverted horizontally, indicate the presence of compacted layers.

Perched water table

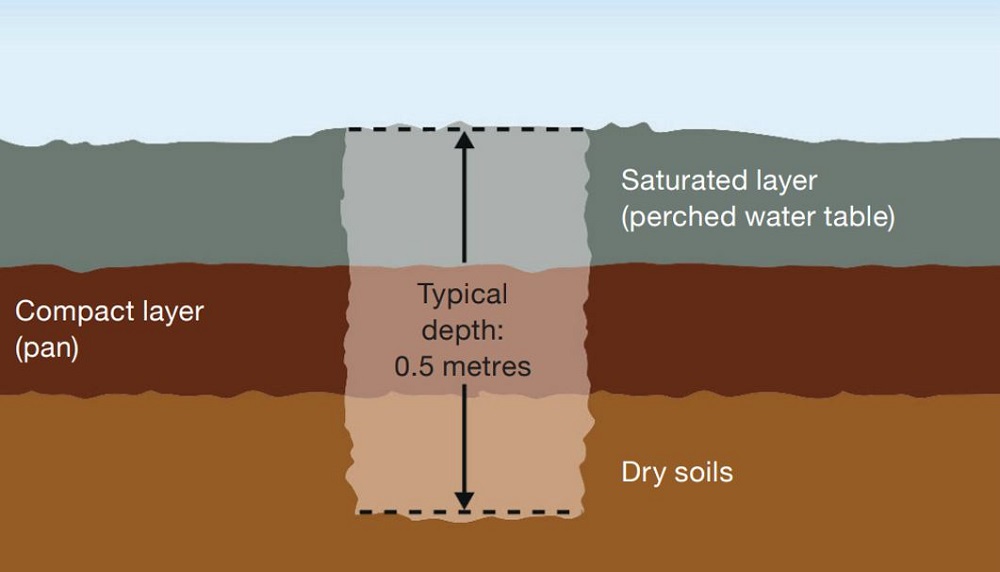

A perched water table is where compaction limits water infiltration, resulting in saturated soils overlying an area of dry soil.

Soil compaction occurs when soil particles are compressed, reducing the space (pores) between them. This restricts the movement of air and water through the soil.

When soil water is present, dig a pit (to a depth where the soil becomes drier) to aid diagnosis.

Saturated soils overlying a layer of dry soil after a period of heavy rain may indicate the presence of a compacted layer preventing drainage.

Illustration of a soil inspection pit

AHDB

AHDB

Compacted layers (pans)

It is not uncommon to find naturally and artificially compacted layers (pans) in susceptible soils.

Natural pans are often very hard bands of soil particles cemented together by iron and manganese.

Artificial compacted layers (known as plough pans) are dense layers caused by farm machinery operation; often 50 to 100mm thick. They generally have a platy structure and frequently contain crop residues.

Compacted layers, whether artificial or natural, can restrict water from reaching underlying drainage systems, limit water infiltration and/or root growth.

If compacted layers are identified, remedial action should be undertaken using targeted subsoiling or topsoil loosening. This should be done before considering field drainage maintenance or installation.

Intercepting springs

Drains can be used to intercept springs before they reach the surface. This helps prevent erosion, localised waterlogging and poaching. The intercepted water, if clean, may be used as drinking water for stock.

Topics:

Sectors:

Tags: