Are consumers’ purse strings about to tighten?

Tuesday, 10 September 2019

In this round up, we look at some key indicators to gauge the UK’s economic performance, what this means for consumers and the outlook for the months ahead, especially given the backdrop of Brexit uncertainty.

In recent months, according to the ASDA income tracker[1], family spending power in the UK has averaged 4.2% higher year on year in Q2 2019. This is mainly due to an increase in wages and higher household incomes rather than lower household expenditure. An increase in discretionary income means a higher likelihood of spending more on leisure and/or activities such as eating out, as well as the weekly shop.

Unemployment figures have been the lowest since the early 1970s, however, there are some signs that things could be about to change. The number of vacancies have been falling and a decline in wage growth is expected in the coming months.

The latest figures from the Office of National Statistics showed that UK GDP in Q2 2019 contracted by 0.2% - the first fall since Q4 2012. This comes after the 0.5% quarter on quarter growth in Q1 2019, mainly due to businesses bringing forward activity and building up stocks ahead of the previous Brexit deadline of 29 March. The probability of the UK leaving the EU with no deal has considerably increased since the new Prime Minister has taken office. Various analyses, including that by the government’s own watchdog, the Office of Budget Responsibility, point to a recession if there is a ‘no-deal’ Brexit.

In Q3 2019, with the latest Brexit deadline of 31 October fast approaching, there could be a repeat of the stockpiling and increased manufacturing output seen in Q1. Nevertheless, the Bank of England has warned of a one in three chance of a UK recession in Q1 2020, even if there is a Brexit deal due to the prolonged uncertainty the economy has faced.

A recession, defined as two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth, would no doubt affect consumer spending power, and so the increase in discretionary incomes seen recently is likely to take a hit.

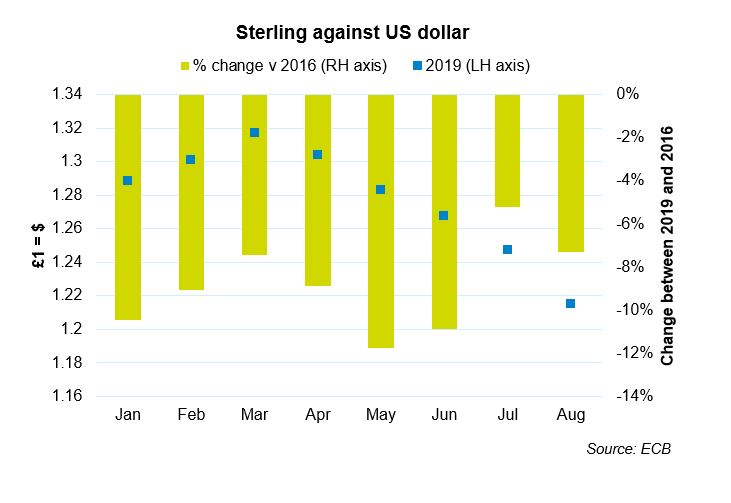

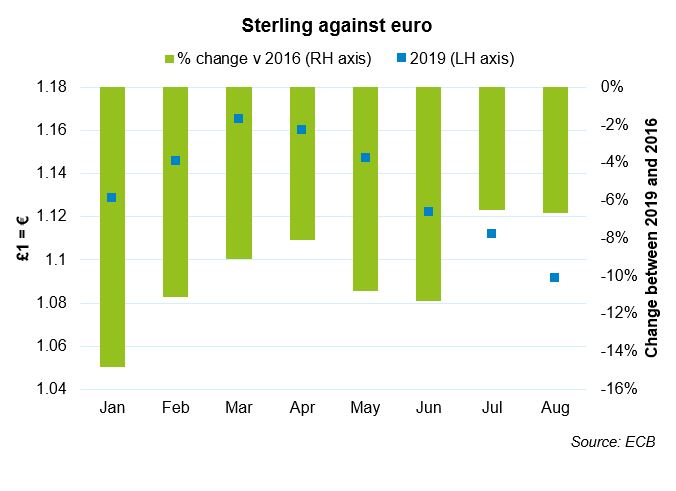

On top of this, the pound has weakened against both the euro and dollar. This makes exports more competitive but imports more expensive. Overall, the UK is a net importer of food, especially beef, pork, fruit and vegetables, so we could see a rise in prices.

Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank of England has recently stated that a ‘no-deal’ Brexit could be less severe the originally thought. For example, it’s now expected that UK GDP could drop by 5.5% rather than 8%. Food prices may also not rise as much as previously thought; weaker sterling and tariffs could contribute to a 5-6% rise in food prices (compared with an earlier estimate of a 10% increase). The rationale behind the downgrading of the potential effects of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit on the economy is due to the increase in preparations for the worst-case scenario. However, it’s important to remember that this is still just an estimate and the real proof of the pudding will be if a ‘no-deal’ exit actually plays out.

As well as currency, additional trade costs could be passed down to consumers. In mid-August, Lidl sent a letter to its suppliers asking for confirmation that they would bear the brunt of any costs associated with the higher trade friction associated with a ‘no-deal’. If this is confirmed and other retailers follow suit, then consumers may be protected from price rises on this front.

However, currency movements are another issue. Economists believe, there is room for the pound to fall further if the prospect of ‘no-deal’ becomes a reality. This could lead to the purse strings of consumers being squeezed.

Nevertheless, KPMG’s latest economic outlook forecasts that if a deal is reached before 31 October, UK GDP could see growth of 1.5% in 2020 as business investment decisions and export orders which have been mothballed due to uncertainty would be able to go ahead and play ‘catch up’. So, it will be a case of ‘wait and see’ over the next month or so as to which of these outcomes actually materialises.

[1] The Monthly ASDA Income Tracker looks at discretionary income i.e. how much money an average household has to spend after taxes and essential costs such as groceries, utilities, transport, rent/mortgage are taken into account.

Topics:

Sectors:

Tags: