- Home

- Knowledge library

- Government policy and its impact on business

Government policy and its impact on business

The agricultural policy landscape is changing in the UK. The beef and lamb sectors were most dependent on direct payments under the EU, so they will be most exposed to these changes. This analysis examines the long-term economic influences on the beef and lamb sectors, including policy change, food security and self-sufficiency.

Key points

- Beef and sheep farmers in England depended on direct payments under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) more than other sectors, so they have been the most exposed to subsequent changes in government policy

- England’s ELMS payments are not a replacement for direct payments

- The focus on food security and maintaining the UK’s current level of self-sufficiency should ensure the most efficient producers in the industry continue to thrive and serve both the domestic market and export markets

How is agricultural policy changing and how could this affect businesses?

Since the UK left the EU in January 2020, the Common Agricultural Policy ceased to apply within the UK. Agriculture is a devolved responsibility, and England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have all started to develop their own policies.

In England (where AHDB collect a levy from beef and sheep farmers), the creation of ELMS has been based on the principle of paying farmers for the provision of public goods. These payments are not subsidies; rather, they are a correction of a market failure. The free market fails to adequately compensate farmers for the provision of such public goods. Examples include healthy soils, biodiversity, clean air and flood prevention.

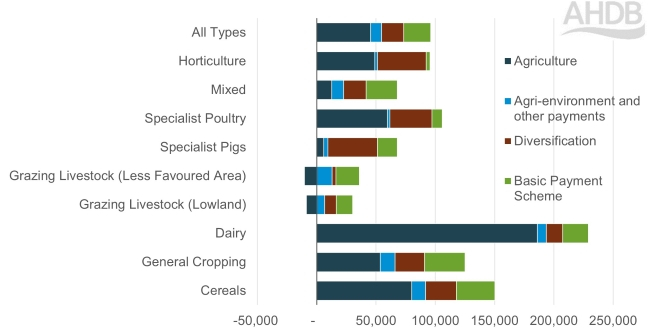

Prior to the UK’s exit from the EU, the grazing livestock sector depended heavily on direct payments to remain financially viable. On average, grazing livestock farmers made a loss from their agricultural activities, and direct payments made up between 86% and 88% of their Farm Business Income (FBI). Figure 1 shows more recent data from 2022/23, indicating that direct payments now make up between 64% and 78% of FBI for grazing livestock farmers as direct payments have been reducing since 2021. We expect this to continue to fall year on year until direct payments are phased out in 2027.

Figure 1. Components of FBI by farming sector in England 2022/23

Source: The Future Farming and Environment Evidence Compendium, Defra

How policy changes are affecting beef and lamb farmers in England, Wales and Scotland

In England, within ELMS, there are three key policies: Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI), Countryside Stewardship (CS) and Landscape Recovery. These schemes reward farmers for environmental actions. The Landscape Recovery scheme is focused more on long-term, large-scale projects, whereas the SFI and CS schemes allow farmers to stack different actions to suit their farm and strategies.

In Wales, the Sustainable Land Management (SLM) framework is the first ever Agricultural Act for Wales and will underpin agricultural support and regulation. As part of this, the Government is establishing the Sustainable Farming Scheme (SFS), which will be similar to ELMS in focusing on rewarding sustainable farming practices and compensating farmers for the provision of public goods such as healthy soils.

Key elements are:

- Sustainable production of food and other goods

- Mitigating and adapting to climate change

- Conserving and enhancing the countryside and cultural resources along with promoting public access and engagement, and sustaining the Welsh language and promoting and facilitating its use

- Maintaining and enhancing the resilience of ecosystems and the benefits they provide

In Scotland, the new agriculture support framework has a proposed four-tier system and is intended to support farmers and crofters in delivering a number of key outcomes in:

- High-quality food production

- Climate change adaptation and mitigation

- Nature protection and restoration

- Improved animal health and welfare

- Wider development of rural communities

The main difference to England and Wales is that 70% of the funding will be paid to Scottish farmers directly via Tiers 1 and 2, which will support farming and support those who are meeting standards relating to climate and biodiversity.

Tiers 3 and 4 will be indirect payments for those who elect to undertake specific actions such as restoring peatland, creating wetland and planting trees.

The Scottish government plans to end Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) payments in 2026 and introduce the new farm support scheme to replace it.

AHDB analysis of SFI (England)

- The SFI alone is not going to be enough to mitigate the loss of direct payments – this is an intentional feature of the scheme. But the right combination of actions could make up a considerable amount of the shortfall

- Taking part in the SFI can provide extra income for beef and sheep farm businesses

- If farmers select SFI actions that are right for their farm, they can considerably boost the farm’s net profit level

- The farm’s net profit will benefit more if SFI actions requiring land are carried out on less productive or unproductive areas of grassland

- It is likely that actions carried out on unproductive grassland will regenerate the land and make it more productive in the long term

- Farmers have the opportunity to maximise the potential of every hectare of land on their farm

- Looking ahead, the SFI can play a role in stabilising farm business incomes

Government spending in England and the devolved governments

There is no doubt that being one of the sectors most exposed to the removal of direct payments, moving to a system of market correction (public money for public goods), which is common across the devolved nations, will be a challenge for the beef and lamb sectors.

Although profit is not the only driver for farmers in the beef and lamb sectors, it is hard to see how many will survive in the medium to longer term without alternative forms of income, be that off-farm, diversification or accessing some of the private funding available from natural capital markets.

We are likely to see some consolidation in the beef and lamb sectors over the next decade. How this will impact overall levels of production will be determined by how farmers approach improvements to efficiency, i.e. the ability to turn inputs into outputs. A key issue for agriculture is government spending. With many domestic issues arising – from cost of living, prolonged inflation, NHS issues and global unrest – there will be many demands on the Labour government’s 2024 budget.

Defra’s budget for England was only guaranteed until the end of the previous Parliament. The new Labour government will decide its own spending priorities. The Budget announcements in October 2024 confirmed that the agricultural budget would remain at £2.4m for the 2025/26 financial year. As discussed in previous AHDB analysis, although the funding pot for agriculture in the UK has remained constant since 2019, farm input costs have increased by 44%. To account for the effect of inflation, the farming budget would need to increase by 44% to £3.4 billion; this is without considering any other spending required to support the farming sectors.

For subsequent years, this funding pot for agriculture could change as the Labour government decides its own spending priorities. However, environment does seem to be a key focus, and the new government has announced a rapid review of the Environmental Improvement Plan by the end of 2024. AHDB will be monitoring future policy announcements closely.

Food security and self-sufficiency

While agricultural policy is devolved, food security is a more centralised issue, albeit closely linked with agricultural policy.

Food security is a broad topic. One of the best definitions was defined at the 1996 World Food Summit:

|

Food security covers global supply and demand, UK supply and demand, international trade, supply chain resilience and social issues around food affordability at a household level. As a levy board, our focus is on the most important aspects to our levy payers: the UK supply base, demand in the UK and overseas, and international trade.

Under the Agriculture Act 2020, Parliament is committed to produce a food security report in the United Kingdom at least once every three years; the next one is due before the end of 2024. The new annual UK Food Security Index (UKFSI) is aimed at complementing the report. The first issue of the UKFSI was published in May 2024.

Self-sufficiency

One key aspect of interest is self-sufficiency. Figure 2 shows self-sufficiency in the UK across various livestock products. The UK does not produce all the food consumed domestically for two main reasons:

- Seasonality: The growing season dictates when products can be produced in this country. The availability of many products, notably fruit and vegetables, depends on imports to fulfil demand at times when they cannot be produced in the UK.

- Consumer preference: UK consumers prefer certain cuts of meat over others, so those cuts in low demand are exported where possible to find a value (e.g. pig trotters). Meat cuts in high demand are imported to satisfy domestic requirements (e.g. high value steak or legs of lamb).

For the beef and lamb sectors, the cost of production affects economic viability. Economic theory suggests that if a country can produce beef or lamb at lower cost than the UK, it makes sense for the UK to import it and focus on producing a product that it is more efficient at producing (the theory of comparative advantage). The UK is not a low-cost producer. However, this needs to be weighed against several factors:

- Security of supply

- The alternative markets the other country may have

- Carcase balance

- Stability of the supply chain at a time of increasing global unrest

- The environmental impact of production

These factors combined in our UK agri-food exports analysis show that domestic production is likely to remain dominant to satisfy domestic consumption in the short term. We will continue to export lamb to EU markets and beyond.

In the medium to longer term, AHDB analysis shows there may be opportunities for exported beef and sheep meat globally.

Figure 2. Domestic production to supply ratios (self-sufficiency) for selected livestock product

for selected livestock products.jpg)