New Zealand agricultural policy

Wednesday, 22 June 2022

New Zealand is a relatively small and sparsely populated economy with per capita GDP slightly above the OECD average. Its market openness is related to its high dependency on international trade. Agriculture has a comparatively high importance to the economy, as it accounts for some 7% of GDP and 6% of employment. Agri-food products account for close to two-thirds of New Zealand’s total exports.

Grass fed livestock products represent the majority of agricultural output. New Zealand is the world’s largest exporter of sheep meat, and one of the largest exporters of dairy products. Beef and horticultural output are also significant exports whereas the arable sector is very small in comparison.

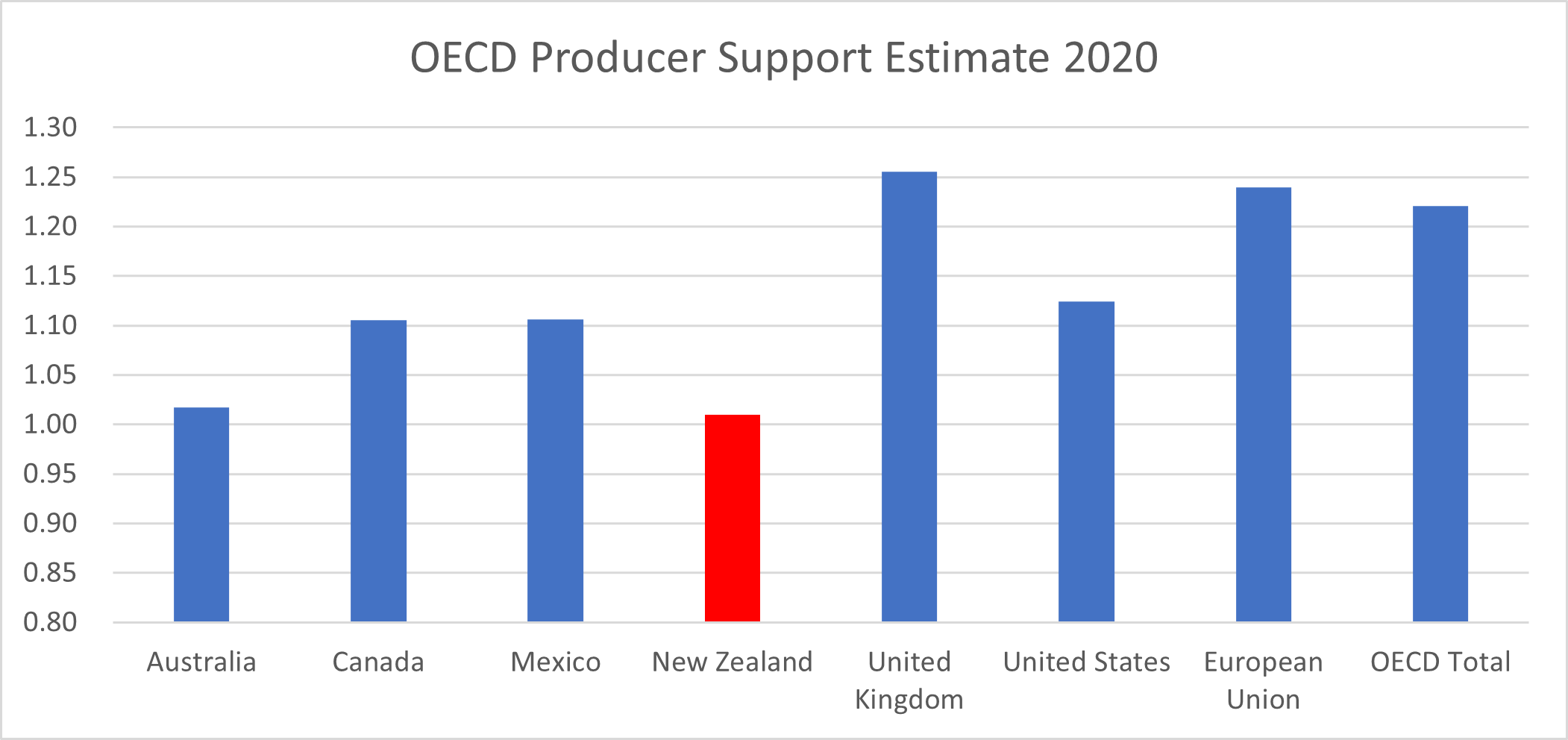

Since the reform of its agricultural policies in the mid-1980s, production and trade distorting policies have almost disappeared in New Zealand, and the level of support to agricultural producers has been the lowest among OECD countries. Over the past decade, this support has consistently accounted for less than 1% of farm receipts, and practically all prices are aligned with world market prices.

The main focus of agricultural policies in New Zealand is on animal disease control, relief payments in the event of natural disasters, and the agricultural knowledge and information system. There is also a strong focus on climate change, with The Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act (ZCA), (2019), making New Zealand one of the first countries to bind its climate commitments into law including objectives for agriculture as an integral component.

Source: OECD Statistics

The transition to this free market approach has not been without challenges for farmers. In the 1970’s, the oil price shock to global economies hit New Zealand hard being so dependent on imported oil. The subsequent accession of the UK to the European Economic Community, at a time when the UK took over 50% of New Zealand’s agricultural exports, forced NZ to diversify across world markets and to adjust its domestic policy.

Initially these policy changes were aimed at boosting production in order to increase agricultural exports and balance the increased cost of imported oil and the loss of significant income from agricultural exports to Britain. A wide range of support mechanisms were introduced, such as minimum prices for agricultural goods, input subsidies, low-interest loans, tax incentives and debt write-offs.

By the mid 1980’s, New Zealand was in an economic crisis, and it was clear that the policy of subsidising agriculture was no longer affordable: the fiscal costs were too high, the sector was becoming increasingly uncompetitive on international markets and resources were misallocated within the sector. Major change began in 1984 with a move towards free market reforms across the economy. For agriculture the reforms included the removal of all price support payments for farmers, lowering or removing tariffs on imported goods and an exchange rate adjustment to make exports more competitive.

The period of reform was painful for New Zealand farmers who saw profits fall sharply. The rural hardship was compounded by low international prices for agricultural products during the middle and late 1980s and by the cost burden of increasing interest rates.

However, despite the government offering exit packages and debt restructuring, only about 5% of farmers left farming – far fewer than predicted. New Zealand has about the same number of people employed in agriculture today as it did in the pre-reform era. Agriculture productivity has quadrupled and the sector’s share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has grown.

Main policy instruments

The New Zealand Government engages with industry and stakeholders across a number of areas impacting agriculture. The main focus is on biosecurity, disaster mitigation, research and development and climate change mitigation. The schemes are often co-funded by industry and government, reflecting the importance of the sector to the NZ economy as a whole.

The Government Industry Agreement for Biosecurity Readiness and Response (GIA) has established an integrated approach to preparing for and effectively responding to biosecurity risks, through voluntary partnerships between the government and primary industry sector groups

Pastoral Genomics is a New Zealand partnership-funded programme for forage improvement through biotechnology. It is funded by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE), DairyNZ, Beef+Lamb New Zealand, Grasslands Innovation, NZ Agriseeds, DEEResearch, AgResearch, and Dairy Australia. The New Zealand Government is investing NZD 7.3 million (USD 4.8 million) between 2015 and 2020 through the MBIE partnerships scheme. This funding is being matched by industry co-funding.

The New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme (NZ ETS) is New Zealand’s main policy tool to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. It requires agri-food companies (e.g. meat processors, dairy processors, nitrogen fertiliser manufacturers and importers) to report on their agricultural emissions, however these companies are not required to pay for their emissions.

The New Zealand Government continues to research and develop mitigation technologies to reduce agricultural GHG emissions. It primarily does so through the New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre (NZAGRC), the Pastoral Greenhouse Gas Research Consortium (PGgRc), and in co-ordination with the 61 member countries of the Global Research Alliance on Agricultural Greenhouse Gases (GRA).

The New Zealand Fund for Global Partnerships in Livestock Emissions Research (GPLER) co-funds internationally collaborative research into how to mitigate GHG emissions from pastoral livestock farming. GPLER is an international research fund set up by the New Zealand Government in support of the GRA.

Recent policy development

Perhaps the most significant policy development in recent years has been the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act (or Zero Carbon Act, ZCA), passed in 2019. The Act sets separate long-term emission reduction targets for long-lived and short-lived GHGs, including a target for biogenic methane. These targets are consistent with the Paris Agreement’s objective of limiting global warming temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

The Zero Carbon Act – implications for the agri-food sector

The Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act (ZCA), passed in November 2019, makes New Zealand one of the first countries to bind its climate commitments into law including objectives for agriculture as an integral component. To help meet these commitments, the government has introduced another Bill, to price agricultural emissions and work with the agricultural sector to achieve the targets for agricultural emissions.

The ZCA sets dual national targets to reduce greenhouse gases (GHGs). They aim to reduce biogenic methane by 10% by 2030 and by between 24% and 47% by 2050, relative to 2017 levels, and to reduce all other GHG emissions to net zero by 2050.

Almost half of all GHG emissions in New Zealand originate from the agricultural sector, and more than a third are in the form of methane from the dairy, sheep and beef industries. Most of the remaining agricultural emissions are in the form of nitrous oxide linked to fertiliser use and urine patches on pasture. While emissions from agriculture have stabilised in recent years, they increased by 13.5% from 1990 to 2017. This period saw a 650% increase in the application of synthetic nitrogen fertiliser and a 60% expansion of the dairy herd (the increases were partially offset by a 53% reduction in the sheep flock and 21% reduction in the non-dairy cattle herd since 1990). With almost two-thirds of all New Zealand exports being agro-food products, originating to a large extent from the livestock sectors, trade-offs being considered in the development of the national mitigation policy are considerable for the economy as a whole and the rural economy.

The Interim Climate Change Committee (ICCC)1 was established in 2018 to provide recommendations on ways to reduce emissions, including from agriculture. It concluded that on-farm emission reduction is most efficiently achieved through emissions pricing – pricing would drive innovation, reward farmers who significantly reduce emissions, and give them autonomy over actions on their farm. The ICCC noted that pricing should be part of a broader package that includes tools, support and advice to farmers (ICCC, 20191). The ICCC noted that it would take until 2025 to implement a farm level pricing scheme and recommended that agricultural emissions be priced at the processor level in the interim.

Following the ICCC’s recommendations and a proposal from primary industry organisations representing all farmers, the New Zealand government introduced, in October 2019, the Climate Change Response (Emissions Trading Reform) Bill (ETR) to price livestock emissions at a farm level, and fertiliser emissions at a processor level, from 2025. A pricing scheme is to be designed through a Joint Action Plan and in collaboration with a group of leading primary industry organisations. The Plan should also include on-farm programmes to support farmers to be ready for emissions reporting and pricing by 2025. The system would grant farmers 95% of their emission credits for free with the remaining credits to be purchased. In the longer term, the share of emission credits to be purchased by farmers would increase, in line with the approach taken for other industries.

The Climate Change Commission is to monitor the progress being made under the Joint Action Plan and report back to the government in 2022. Should progress be considered inadequate, the government retains the option to impose pricing at processor level. The Minister for Climate Change is also to report back in 2022 on the details of a farm-level emissions pricing scheme, including details of an alternative pricing scheme to the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme.

Source: OECD

The rural economy has transformed since the removal of production-based subsidies. Agricultural production is run as any other business; production decisions and market returns are dictated by the domestic and overseas markets. Sales depend on meeting customers’ expectations of price, quality, integrity of the supply chain and sustainability. Further, the New Zealand regulatory model, which is a preventative risk and science-based system, places responsibility on producers to demonstrate compliance with standards. This encourages businesses to understand the risks associated with their products and production processes and account for them within their businesses.

Note 1: As of December 2019, the Interim Climate Change Committee was disestablished and replaced by the independent Climate Change Commission, a government funded body set up under the Zero Carbon Bill to provide the government with advice on climate policy. The Commission is made up of a Chair and six Climate Change Commissioners who are experts in climate science, adaptation, agriculture economics and the Maori-Crown relationship.

Topics:

Sectors:

Tags: