- Home

- Knowledge library

- How to promote and measure root growth and distribution in cereals

How to promote and measure root growth and distribution in cereals

Ensuring that wheat and barley crops have well-developed root systems is essential for optimum water and nutrient capture. An understanding of the factors that influence root growth in the soil makes it easier to identify management interventions.

Growth guides for wheat, barley and oilseed rape

Root growth up to stem extension

Benchmark: 15 km winter wheat roots/m2 at GS31 (0.5 t/ha)

Varietal influence: Low in winter wheat, medium in barley

Other influences: Sowing date, soil structure, plant population, phosphorus (P) availability and, for winter wheat, take-all

Roots begin to grow at germination, with three to six main (seminal) roots emerging before the second leaf appears. These can grow deep and persist throughout the crop’s life.

In deep, warm, well-structured soil, where water supply is not limiting, main roots grow quickly in the autumn (12 mm/day), slowing during winter (6 mm/day), before increasing in the spring (18 mm/day).

The number of crown roots, which develop from the stem base, relates to leaf and tiller numbers. Once the main shoot has three to four leaves, crown roots appear with thickened upper regions to anchor the plant.

A mature root system has 20 or more roots on each plant, plus numerous branches.

By growth stage 31 in winter wheat, maximum rooting depth can exceed 1 m and root dry weight is about 27% of shoot dry weight.

Root growth after stem extension

Benchmark: 31 km winter wheat roots/m2 at GS61 (1.0t/ha)

Varietal influence: Low in winter wheat and medium in winter barley

Other influences: Sowing date, plant population, soil structure, PGRs/fungicides and, for winter wheat, take-all

During stem extension, roots grow rapidly. Root extension and branching increase as soil temperatures rise.

This is the main period of crown root production. During this period, dry matter may be lost as some roots die, and as assimilate is exuded or respired.

In winter wheat at growth stage 61, root dry weight is 1.0 t/ha but twice as much assimilate may have been used in root growth.

With typical root distribution, total root length reaches 31 km/m2 by anthesis and maximum rooting depth reaches 1.5–2 m. Over 70% of root length is found in the top 30 cm of the soil.

After anthesis, root growth slows down – only 10% total assimilate produced during grain filling is used by the root system.

As roots in the topsoil begin to die, those in the subsoil may continue growing.

Protecting leaves with fungicides can prolong root growth and nitrogen uptake after growth stage 61.

Root length density (RLD)

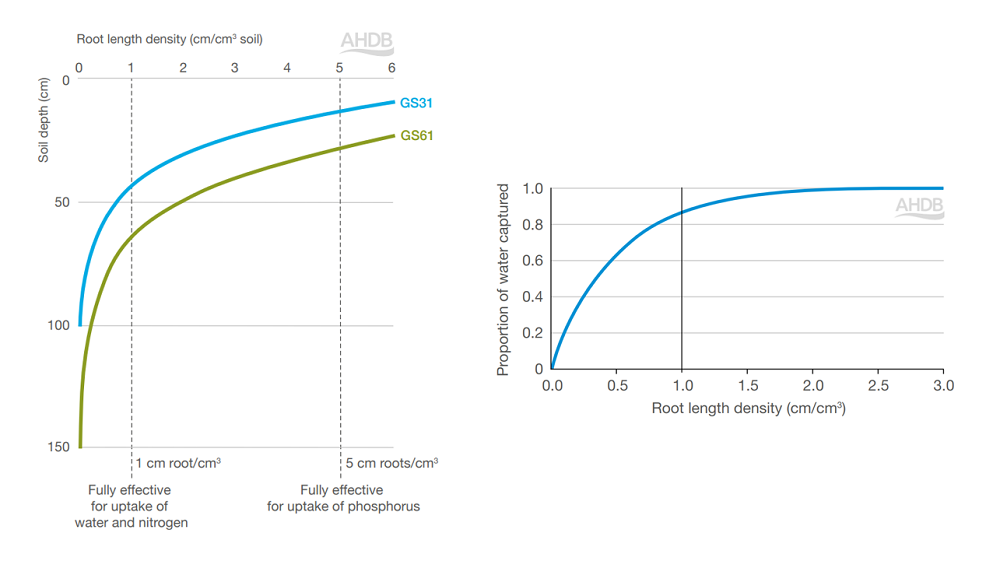

High rates of uptake of the less mobile nutrients, such as phosphorus (P), only occur when root length densities (RLDs) exceed 5 cm/cm3 of soil.

Lower root length densities are adequate for potassium (K) uptake and about 1 cm/cm3 is needed for the take-up of most of the available water and water-soluble nutrients, such as nitrogen.

Lower RLDs will take up less of the available water and nutrients.

Maximising root growth in the subsoil significantly improves soil water supply to the crop.

Factors that increase root-lodging risk

Root lodging is when the root system has insufficient anchorage to hold up the plant against leverage.

It is often made worse by windy and wet conditions. Just 6–11 mm of rain in a day reduces soil surface strength and significantly increases the risk of root lodging.

Root systems with greater spread (depth and width) are less prone to root lodging. Soils with good crumb structure, low clay content or high organic matter tend to provide less anchorage, increasing lodging risk.

An introduction to lodging in cereals

How to measure rooting

To conduct a visual assessment, dig up representative plants (within a couple of months of planting) – ether based on soil type or crop growth.

Measure rooting depth and weigh the washed roots to obtain root biomass.

If a soil core is available, soil can be extracted to 90 cm in the spring and before harvest to assess changes in soil moisture as a proxy for rooting depth.

Alternatively, soil structure can be assessed as a proxy for rooting, as good soil structure will allow the roots to penetrate to depth more easily and capture available water.

Soil factors that influence rooting

Soil structure has a major impact on root growth and distribution.

In some clay-rich soils, moisture extraction by roots promotes cracking, which improves soil structure and root access in following seasons. Hence, deep rooting can be self-sustaining, unless wheelings or cultivations destroy soil structure.

With minimal tillage, enhanced earthworm activity creates long continuous pores in the subsoil to aid root penetration.

GREATsoils: AHDB information to help you protect soil and improve its productivity

Topics:

Sectors:

Tags: