Economic outlook – February 2024

Thursday, 8 February 2024

The UK saw significant economic unrest in 2023. With inflation remaining high and interest rates at levels not seen for decades, the cost-of-living crisis was a major concern for consumers and businesses in the UK. Are we to expect better news in 2024?

The higher interest rates in 2023 dampened down the demand-pull inflation as consumers cut back on purchase decisions. But cost-push inflation – first in the form of higher fuel costs, and then in higher wage demands as workers attempted to keep pace with the rising cost of living – remained stubbornly high until late 2023. Gross domestic product (GDP) growth was flat, raising fears of the economy tipping into recession.

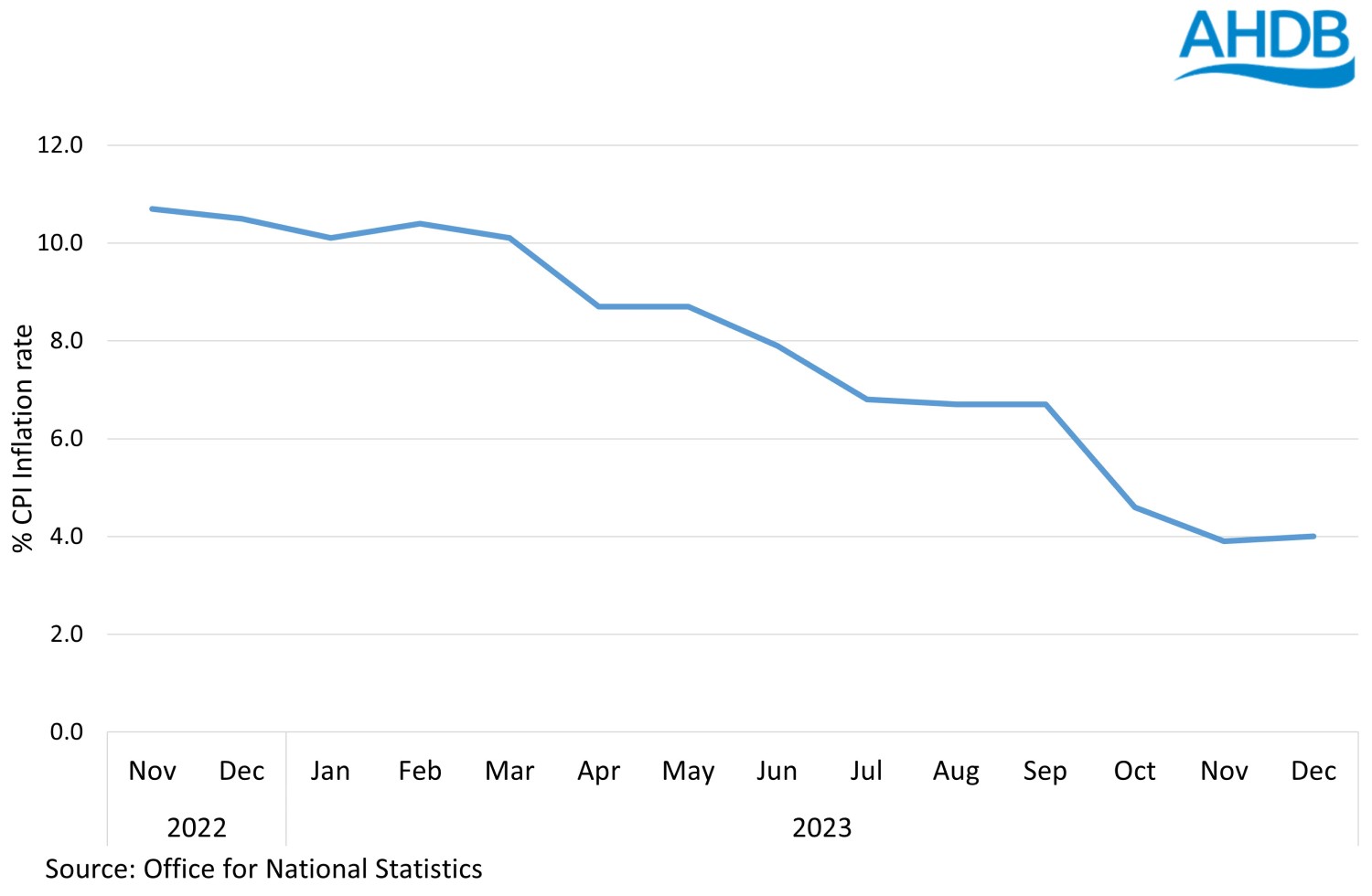

In the last months of 2023, however, inflation dropped significantly (to 3.9% in November). It did then rise to 4% in December, rather than continuing its expected downward trajectory. We look ahead to discover whether 2024, especially being an election year, will look brighter for the economy.

Figure 1 shows the fall in inflation in 2023, as shown by the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Figure 1. CPI falls throughout 2023

Inflation and interest rates

Inflation, as measured by the CPI, rose in 2023 and peaked in October 2022 at 11.1%. This led to several increases in Bank of England base rates in an attempt to contain inflation, taking the current rate to 5.25%. The slowing of inflation to 3.9% in November 2023 suggests that interest rates are finally taking effect, although there was an unexpected uptick to 4% in December.

December’s unexpected rise has not decreased the likelihood of more interest rate cuts in 2024. However, it is a fine balancing act. Any reduction in interest rates will depend on GDP growth and wage demands; the latter are still rising as consumers attempt to remedy both their real loss of income and the erosion of living standards that persistent inflation creates. While inflation is still above the 2% Bank of England target, and above the European average, a reduction is unlikely in the short term. The next move is likely to be downwards, sometime in spring 2024. Any reductions will be incremental: we are not likely to return to the historically low interest rates seen pre-2023.

This scenario of gradual reduction in inflation and the downward pressure on interest rates is threatened by the potential for prolonged escalation of the Israel/Gaza conflict.

It is important to remember that inflation is an average measure based on a representative ‘basket’ of goods and services. Individuals experience inflation differently, depending on their spending patterns. Those spending proportionately more of their income on food, for instance – predominantly the less well off in society – will experience higher levels of inflation than those who are better off. This is because food price inflation rose well above the average CPI inflation in 2023, driving the cost-of-living crisis.

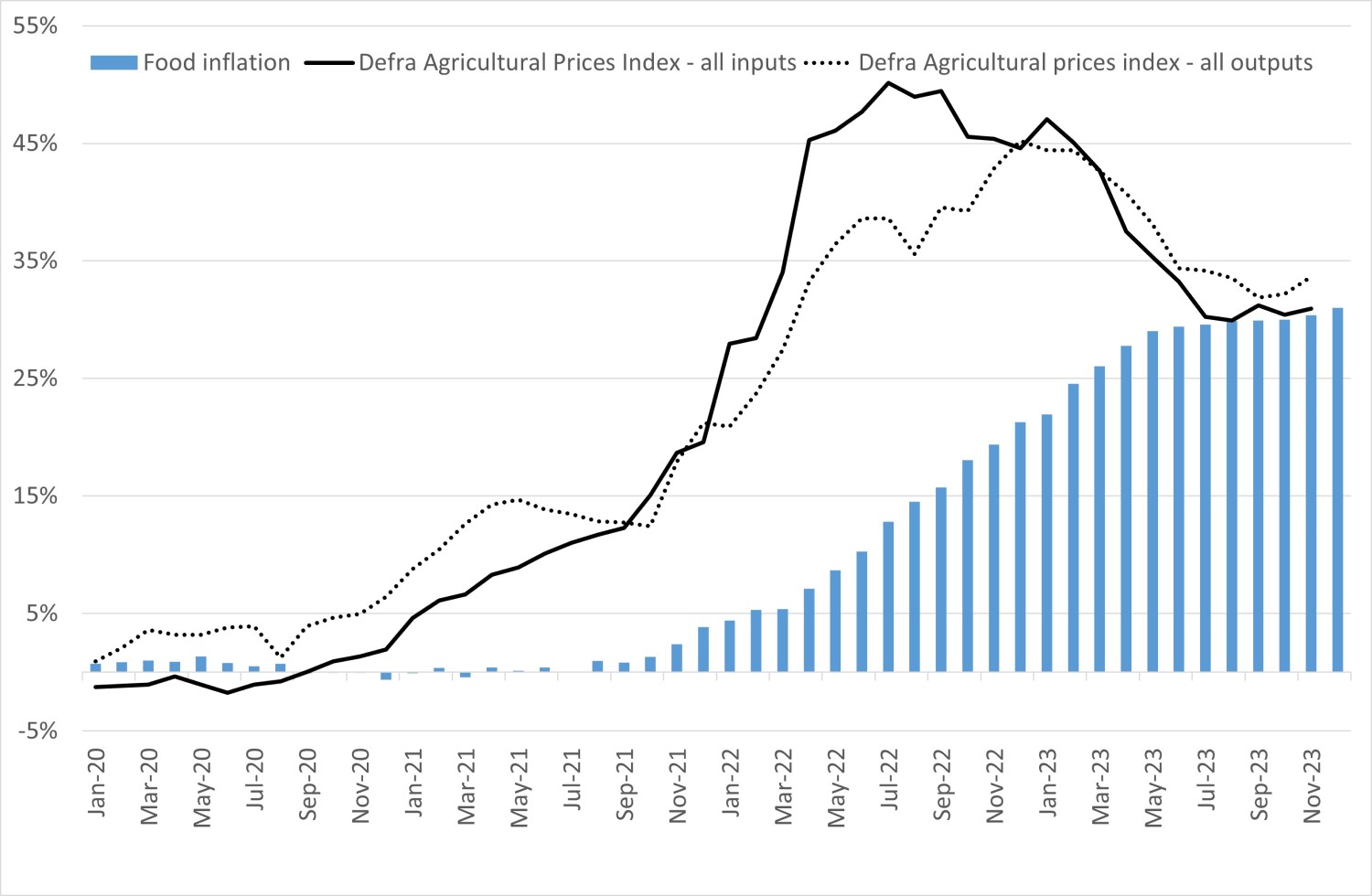

Similarly, farmers faced soaring input costs in 2023, which have persisted far beyond what annual inflation statistics might portray. Figure 2 shows agricultural input inflation and food inflation since 2019. This is the total amount of inflation since 2019 rather than the latest annual inflation. Agricultural input costs are analysed using Defra’s Agricultural Price Index (API) and it should be noted that labour is not included in this data set.

Compared to 2019, both farming inputs and food prices have increased by over 30%, which is striking considering that these items typically operate around 0% in the modern age. While some inputs have begun to fall back in price, it currently feels unfathomable that things will return to the 2019 norm.

Figure 2 considers the whole of the input and food category, and undoubtedly different inputs and products will be subject to different inflationary levels.

Linked to the biological systems at play, a lag of around a year can be seen between the onset of inflation of inputs and that of food. This is pertinent from a food security point of view, as impacts on global input prices should be considered early indicators for food market impacts.

Figure 2. Inflation in agriculture

Source: ONS, Defra

Growth in 2023

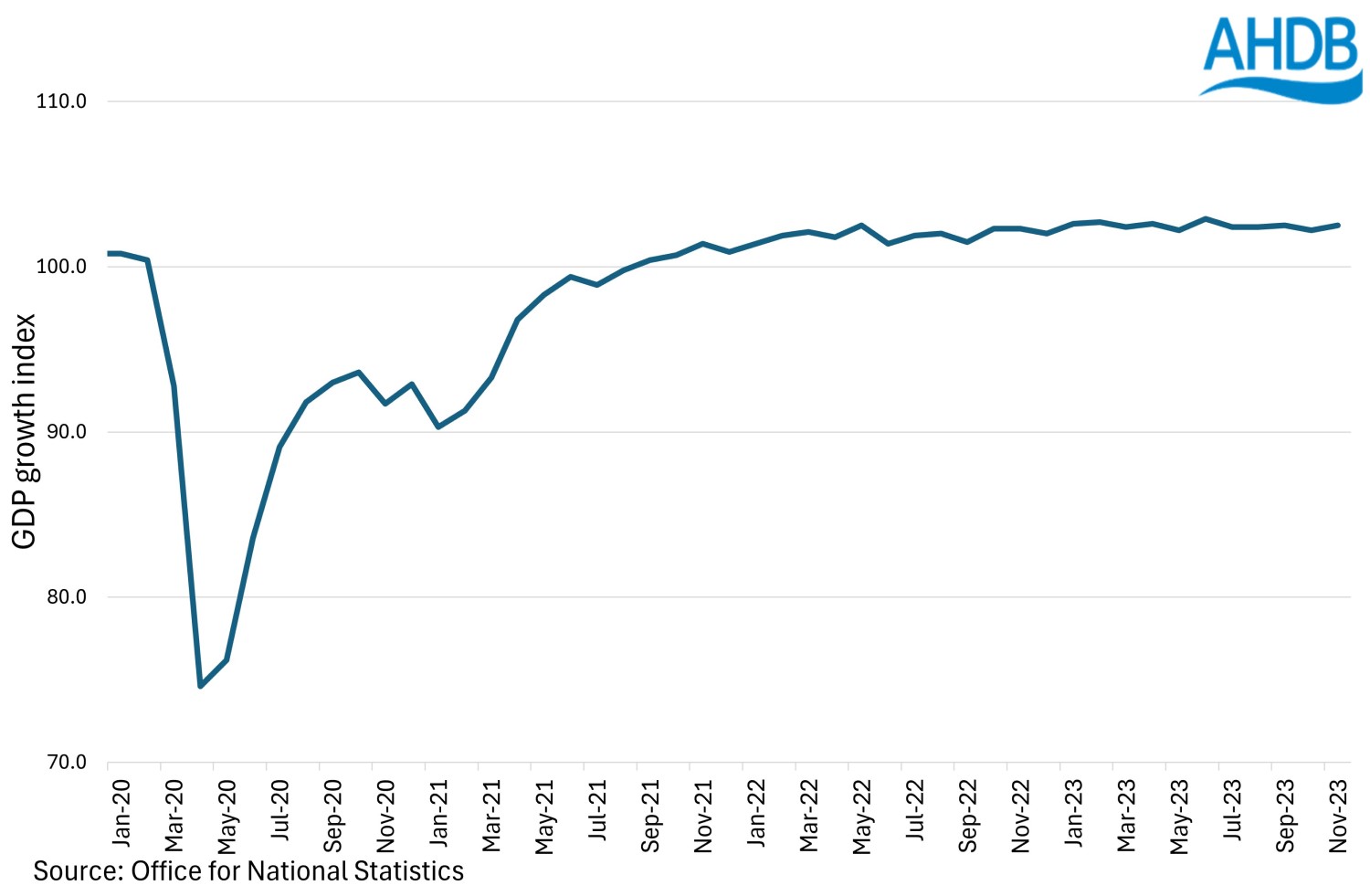

UK GDP showed no growth in Q2 2023 and fell by 0.1% in Q3 2023. Real GDP is estimated to have fallen by 0.2% in the three months to November 2023, compared with the three months to August 2023. Monthly data for November shows GDP growing by 0.3%. Whether we will technically enter recession by the end of 2023/24 is a moot point. Figure 3 shows GDP growth is flat, and the outlook suggests this will continue for the foreseeable future.

The rate of wage growth (on average) is outstripping inflation, but many households will face a hike in mortgage payments as they come to the end of fixed-rate deals in 2024. This means that consumers will likely remain cautious about spending throughout 2024 and this will limit economic growth.

The potential for prolonged escalation of the Israel/Gaza conflict will likely result in a return to higher inflation. With UK prospects for growth already limited, any disruption is likely to drive inflation higher and economic growth lower. This results in ‘stagflation’: an economy that is not growing, coupled with rising costs of food, fuel and clothing.

Stagflation is considered by economists to be more damaging to an economy than a recession, as it combines all the negative effects of recession with a higher cost of living. Stagflation can lead to rising unemployment and lower real wages.

Figure 3. GDP growth index 2020–23

Employment

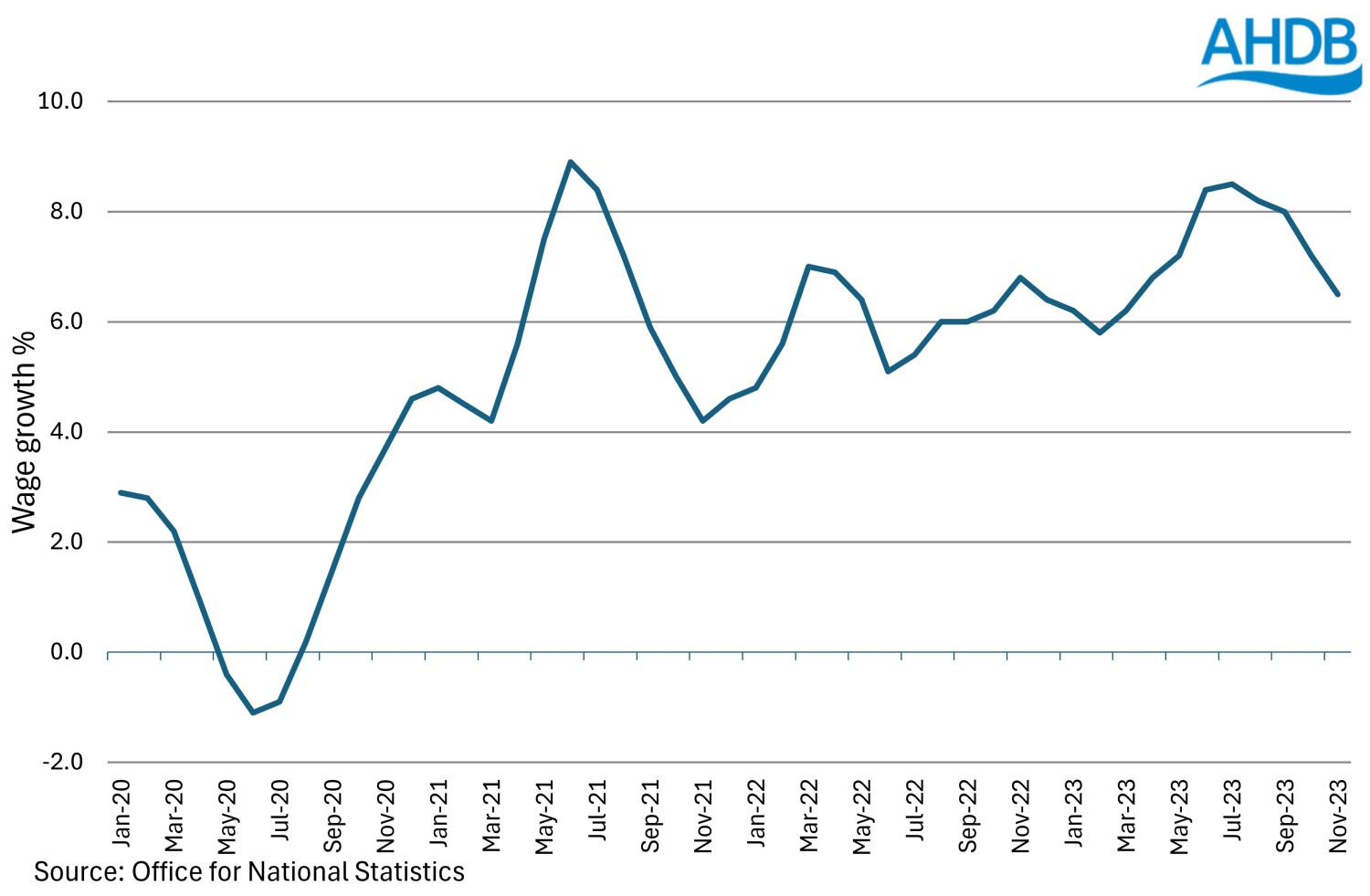

At the time of writing, wage rates are rising in the UK faster than inflation, and unemployment is low. Workers’ demand for increased wages is in response to the rising cost of living.

This is a significant issue for the economy, because one of the major components of businesses’ costs of production is their wage bill. This increased cost could be pushed onto consumers, which could keep prices rising.

The combined effect of EU exit and the Covid pandemic has created a skills shortage in the UK. There are fewer workers available, both from the EU and from the domestic workforce – one reason being that almost 8.7 million workers aged 16–64 are now economically inactive.

Tighter labour markets mean workers can negotiate higher wages. But if economic growth remains low and inflation continues, demand within the economy will drop and unemployment could rise.

Figure 4. UK percentage wage growth 2020–2023

Summary

Barring the risk of an escalation of hostilities in the Middle East, 2024 appears to be a year of flat GDP growth and gradually reducing inflation.

Living standards will continue to be squeezed throughout the year.

Interest rates are likely to come down gradually. But the Bank of England will be watching the inflation data closely and is likely to take a cautious approach to these reductions, particularly if the Government announces tax cuts in the run-up to an election.

Sectors: