What do Rules of Origin mean for UK milling?

Monday, 29 March 2021

Prior to the UK’s exit of the EU, we looked at potential impacts on the UK milling and malting sectors. Now, with a trade deal in place with the EU, we have a clearer picture in place. While the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement allows tariff free trade to continue, certain criteria such as Rules of Origin, now have to be met to access this preferential treatment. In this article, we look at the implications for the UK milling sector.

Background

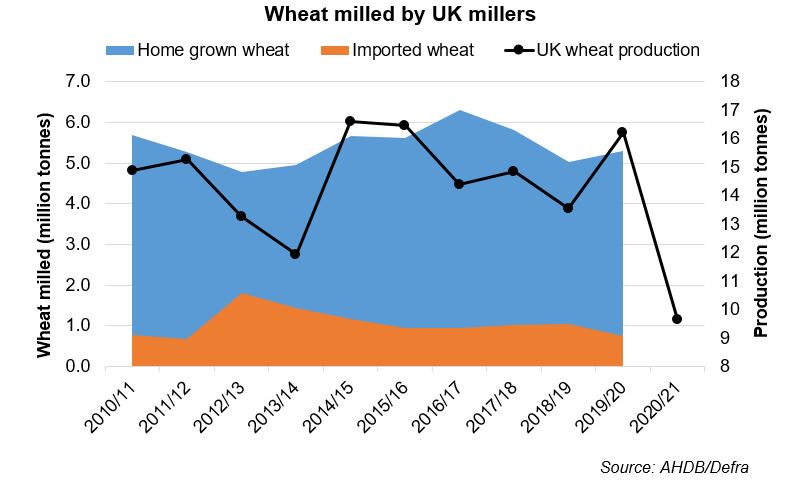

In the past 10 seasons, the proportion of imported wheat milled by UK millers has averaged around 16%. Over the past decade, UK wheat production has averaged 15Mt, although in 2012/13 and 2013/14, in particular, a smaller wheat crop meant higher imports. With the 2020 UK wheat harvest below 10 Mt and the lowest since 1981, UK wheat imports from July to December 2020 were already two and a half times higher year on year and higher than the past two seasons’ import levels. Crop quality is also a factor. Typical proportions of imported wheat milled were around 12-15% in years of a good quality domestic crop, whereas in poor quality years such as 2012/13, the proportion of imported wheat milled was as high as 27%.

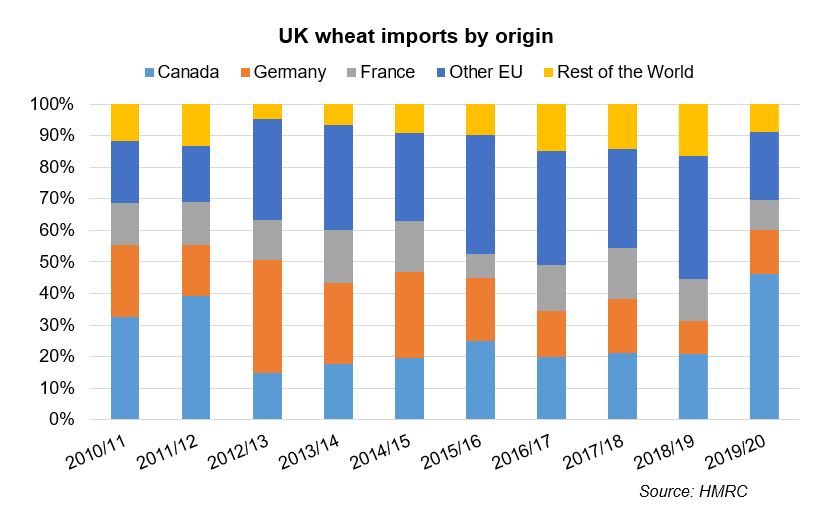

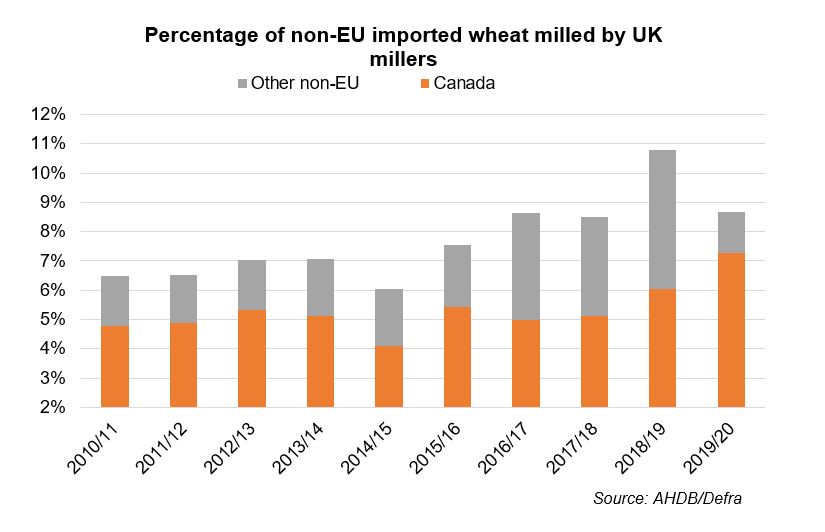

The main origins of UK wheat imports are Canada, France and Germany. Canadian wheat is favoured as it blends well with UK wheat. Furthermore, North American wheat has qualities such as high protein levels and very strong gluten which cannot be sourced in UK wheat and so there will be a proportion of imported wheat from North America year to year.

How does the new trade arrangement affect flour trade?

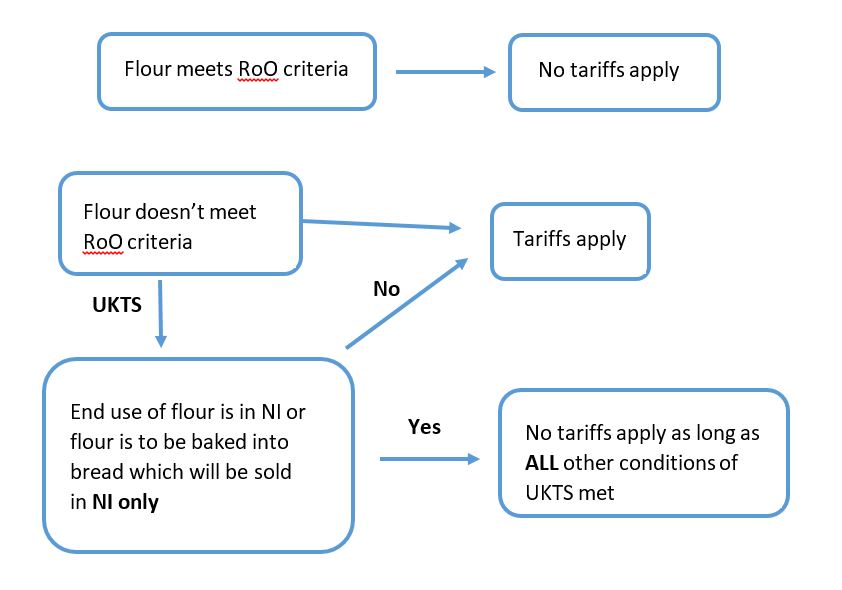

While the EU/UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement allows tariff free trade between the EU and UK, this is under the condition that Rules of Origin (RoO) criteria are met. Up to 15% of third party wheat (i.e. wheat that is not of UK or EU origin) can be used to produce flour that is eligible to be exported tariff free.

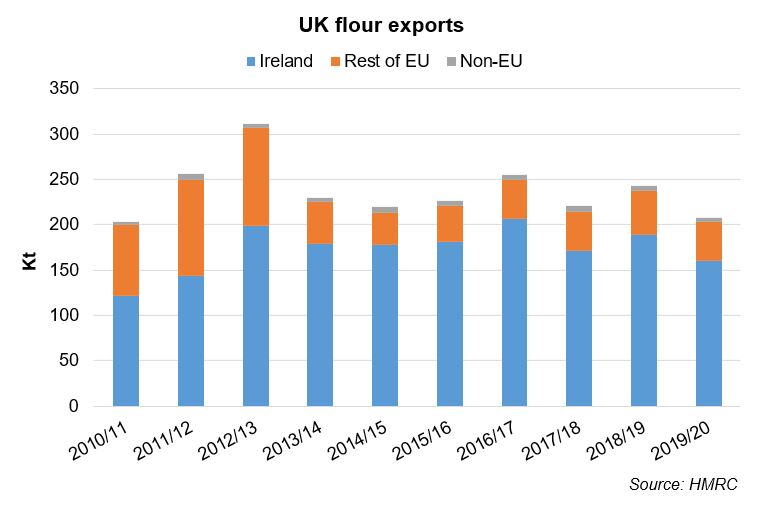

Most of the flour produced in the UK is for domestic consumption. Over the past 10 seasons, on average, only 5% of flour produced in the UK was exported, with most sent to Ireland or other parts of the EU. However, due to the special circumstances arising from trade with Northern Ireland (NI), there are now additional factors to consider.

Under the NI protocol, goods can enter NI tariff free from other parts of the UK unless there is a risk that the good could enter the Republic of Ireland (RoI) (EU) either as the good in question or if it is processed to form another product. The product needs to undergo sufficient transformation in order to qualify for preferential tariff rates.

As the graph above shows, the amount of Canadian wheat used to produce UK flour is most likely to be the component under scrutiny when it comes to determining whether or not UK flour exports meet RoO criteria.

If flour destined for RoI does not meet the criteria, then the EU tariff of €172/t would be applicable. This is now true for flour exports from GB to Northern Ireland unless it can be proved that the flour is not at risk of entering the RoI.

Tariffs on wheat and flour

|

|

UK GT |

EU CET |

|

High quality common wheat |

0 |

0 |

|

Medium quality common wheat |

£79/t |

€95/t |

|

Low quality common wheat |

£79/t |

€95/t |

|

Wheat flour |

£143/t |

€172/t |

The UK Trader Scheme (UKTS) is a mechanism by which traders can declare that their products are ‘not at risk’ of entering the EU via RoI and so qualify for tariff free access, even if the proportion of third party material exceeds the 15% threshold. However, traders need to meet certain criteria such as having a fixed address for the businesses that are being supplied in NI. The end use of the good must be in NI. So, in the case of exported flour containing more than 15% of Canadian wheat, the flour must be used and/or sold in NI only. If the flour is to be baked into bread, then the bread must be sold in NI or UK only – it can’t be sold in RoI.

If the flour is to be used to produce bread that will be sold in NI and RoI, then the conditions of UKTS are not met and so full tariffs will apply on the flour.

A small or infrequent trader could apply for a waiver in order to move goods from GB to NI which do not fulfil RoO criteria. The claim for a waiver needs to be made on the import declaration. Waivers are provided in the form or ‘de minimis’ aid (essentially state aid) which is measured in euros. The maximum amount that can be claimed is €200,000 over three tax years. For primary agricultural production, the limit is €15,000 over three tax years.

If tariffs are wrongly applied to goods moving from GB, or the rest of the world, to NI it may be possible to reclaim this cost. However, the method of reimbursement is not ready for action at the time of writing and there is currently no information of when details will be published.

How much of an issue has this been so far for UK millers?

As the graph below shows, on average, 7-8% of wheat milled by UK millers is from outside the UK or EU. Of course, for individual businesses this amount will vary, but it gives an idea that generally speaking the 15% threshold to meet the RoO criteria for flour exports is unlikely to cause widespread issues.

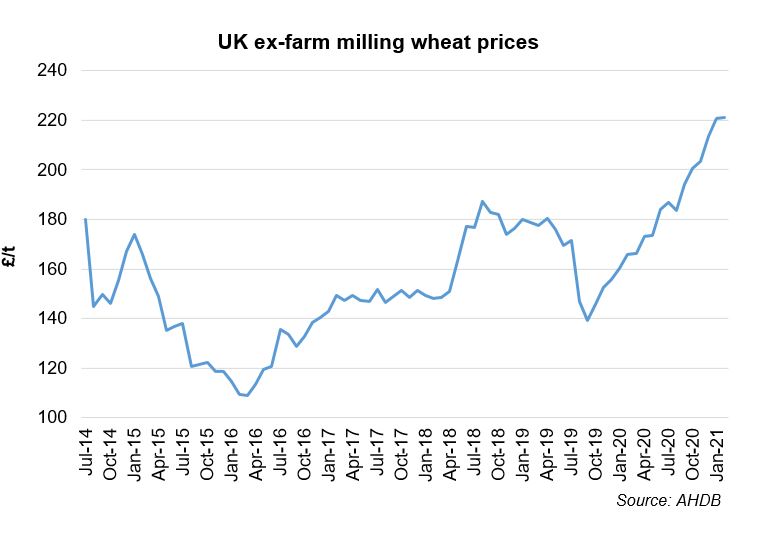

Furthermore, only 5% of flour produced in UK is exported. Flour sent to NI will be included in this figure, so there is extra criteria under the NI protocol to be aware of as mentioned above. Anecdotally, the effect of rules of origin criteria on the UK milling sector has been limited. The sharp rise in wheat prices has been more of an issue.

Nevertheless, businesses which have fallen foul of meeting RoO criteria have suffered a ‘double whammy’ with high export tariffs exacerbating higher raw material prices. Therefore, it’s crucial that traders examine their eligibility under the EU/UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement before exporting.