Stepping forward into regenerative agriculture

Thursday, 4 March 2021

Regenerative agriculture continues to create a buzz. With its potential to drive down production costs, improve margins and increase soil health, no wonder it is being welcomed with open arms by many farmers, supply chains and policymakers. AHDB Knowledge Exchange Manager Teresa Meadows looks closer at the technique with no ‘easy button’.

Last autumn, I attended (virtually) the annual Agri-TechE REAP conference. As usual, it was packed full of people and organisations innovating at the frontier of agriculture. However, I was particularly keen to hear the views of David R. Montgomery during his AHDB-sponsored presentation.

An author and professor of geomorphology at the University of Washington, David has travelled the world to hear how farmers have reversed the fortunes of their soils. Numerous conversations later, he now believes soil-health nirvana can be achieved through the adoption of three general principles of conservation agriculture:

- No or minimal soil disturbance to help soil life flourish.

- Growing ground cover to lock in nutrients and protect the land.

- Using a diverse rotation (three or more crops) to promote life and avoid nutrient overextraction.

Can regenerative agriculture pay?

If a new approach is clearly more profitable, then it has hope. David found that to be the case, as did an article by Claire LaCanne and Jonathan Lundgren published in 2018*. The study described used system extremes to test the difference regenerative agriculture could make.

Corn production in the Northern Plains of the United States is dominated by large monocultures, which are heavily dependent on inputs and tillage. The study compared the ‘conventional’ fields with ‘regenerative’ cornfields, which included three or more compatible practices – such as planting a multispecies cover mix, eliminating pesticide use, abandoning tillage and integrating livestock. However, the conventional cornfields applied none or only one of the practices.

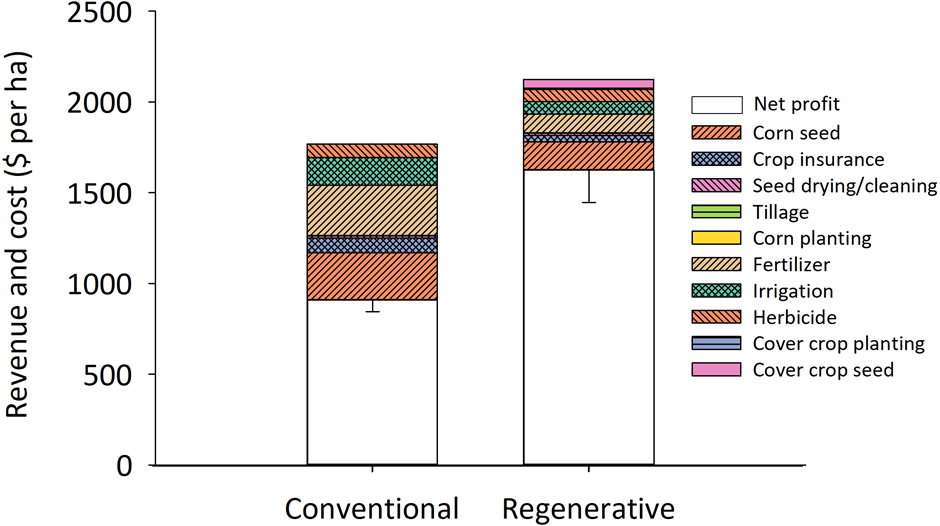

The average gross profits are shown in the chart. The analysis used direct costs and revenues for each field (across all 40 fields in each treatment), and excluded any overhead and indirect expenses.

Headline results

- Regenerative fields had 29% lower grain production but 78% higher profits than the conventional fields

- The profits were largely driven by input savings (fertiliser, pesticides and fuel)

- Profit was positively associated with the particulate organic matter of the soil, but not yield

Figure 1. Revenue and costs for US corn production – ‘conventional’ v ‘regenerative’ system.

Source: LaCanne, C. E., Lundgren, J. G. 2018. Regenerative agriculture: merging farming and natural resource conservation profitably. Peer, J. 6:e4428 doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4428

What about regenerative agriculture in the UK?

As the general principles translate to any cropping situation, they could (in theory) be made to work anywhere. Obviously, UK cropping systems are different from US corn production. However, the fact it does pay in some situations means it deserves our attention. Lessons from early adopters of regenerative agriculture show:

- Yield depression is often seen in the first few years.

- Those who use all three principles from the start tend to record successes more quickly.

- Although the general principles translate to other settings, the specific practices need to be tailored to the specific setting.

With no blueprint available, the sharing of locally relevant experiences is essential – and this is where our Monitor Farm and Strategic Farm network come in. For example, many of our farms look at cultivation approaches, cover crop species/mixtures and rotational design. Across AHDB, the organic and field vegetable sectors also provide a valuable reference source for arable farmers.

Will the technique flounder or flourish?

Regenerative agriculture comes at a time when there is a hunger to move away from the farm-to-a-blueprint approach adopted in the second half of the 20th century. The industry is more business savvy, with greater attention paid to the details and the long-term effects associated with change. Future policy changes, the need to mitigate against climate change and improve our environmental credentials also mean that these kind of techniques are likely to gain increased interest. Then, there is the consumer, who will continue to demand affordable, nutritious and sustainably produced food. Can markets be created that further support development of these techniques?

The approach, alongside integrated pest management (IPM), provides an opportunity for farmers, however, as David concluded: “There is no ‘easy button’, when it comes to implementing regenerative farming”. Those who use their independence, intelligence and ingenuity to learn from their own experiences and those of others are most likely to thrive. And David certainly believes that regenerative agriculture could win out.