When big is not beautiful

Monday, 22 August 2022

Enlightened farmers and geneticists are united in their campaign to reduce the size of Holstein cows across the national herd.

Big cows are harder to manage, less efficient and have higher costs of production than their smaller cohorts. Yet, still the size of dairy cows in the UK continues to rise, despite industry efforts to halt this trend. This applies to stature, as well as overall weight.

Farmers have been warned that if they continue to breed larger cows, it will threaten their long-term ability to manage their herds and could even compromise their livelihoods. Carbon footprint will worsen, feed consumption will disproportionately increase and overall efficiency will decline.

Both geneticists and farmers who recognise the importance of moderating the size of dairy cows struggle to understand why the upward trend continues.

Keith Gue, who farms in Sussex, says it’s unfathomable that most farmers, especially in the current economic climate, continue to choose to increase the size of their cows.

He says: “There’s a huge myth about production being tied to body size. But our biggest cost on the farm is the feed bill so if we can reduce that by reducing the size of our cows, lowering their feed costs, and keeping their production the same, why wouldn’t we?”

He has been putting this into practice across his family’s 420-head, pedigree Huddlestone herd for over 10 years.

He says: “We started excluding bulls moderately positive for stature in around 2010, continued to reduce the stature threshold until in the last five years, we have actively chosen negative stature bulls.”

But his grouse is not just about stature.

“A lot of people have the idea that they need chest width, and I am not sure why,” he continues.

“People love big, old, wide-chested cows but heifers don’t start out like that, and linear type profiles are calculated from heifer classifications,” he says. “In other words, people are trying to breed the cow they want as a fifth calver using the linear of a heifer.”

Instead, he says that when selecting bulls, breeders should look at the traits of stature and chest width in relation to one another, in a balanced way.

“If you select your bulls for increased stature but keep their chest width the same, his daughters will get narrower,” he says. “But if you keep chest width the same while reducing your bulls’ stature, daughters will get relatively wider.”

Remarking that the Huddlestone herd has had to increase its cubicle dimensions despite its efforts to control the size of its cows, he attributes this to both a breeding and management lag, and not having started managing body size as early as he now feels he should.

Today, he believes the perfect bull for his herd has a difference of about 1 point between stature and chest width.

He says: “If we used a -1 stature bull we’d want 0 chest width, or -2 stature with -1 chest width. This means we think a +2 stature bull would need +3 chest width, although that’s not a bull we’re likely to use!”

Further justifying his choices for their management outcomes, he says: “When a big cow goes down, the chances of getting her up are slim, and she has a higher chance of going down in the first place.

“But small cows don’t tend to die. They are easier to handle, to give TLC, they are safer to work with and they fit into our existing system.”

Marco Winters, head of animal genetics for AHDB, backs up these views with data from across the national herd.

He says: “Everywhere I go, farmers tell me they don’t want bigger cows, but all the genetic trends tell us that’s what they are breeding.”

This is despite the fact that a negative weighting for bodyweight is built into national breeding indexes such as £PLI (Profitable Lifetime Index) and should be pulling these traits in a downward direction.

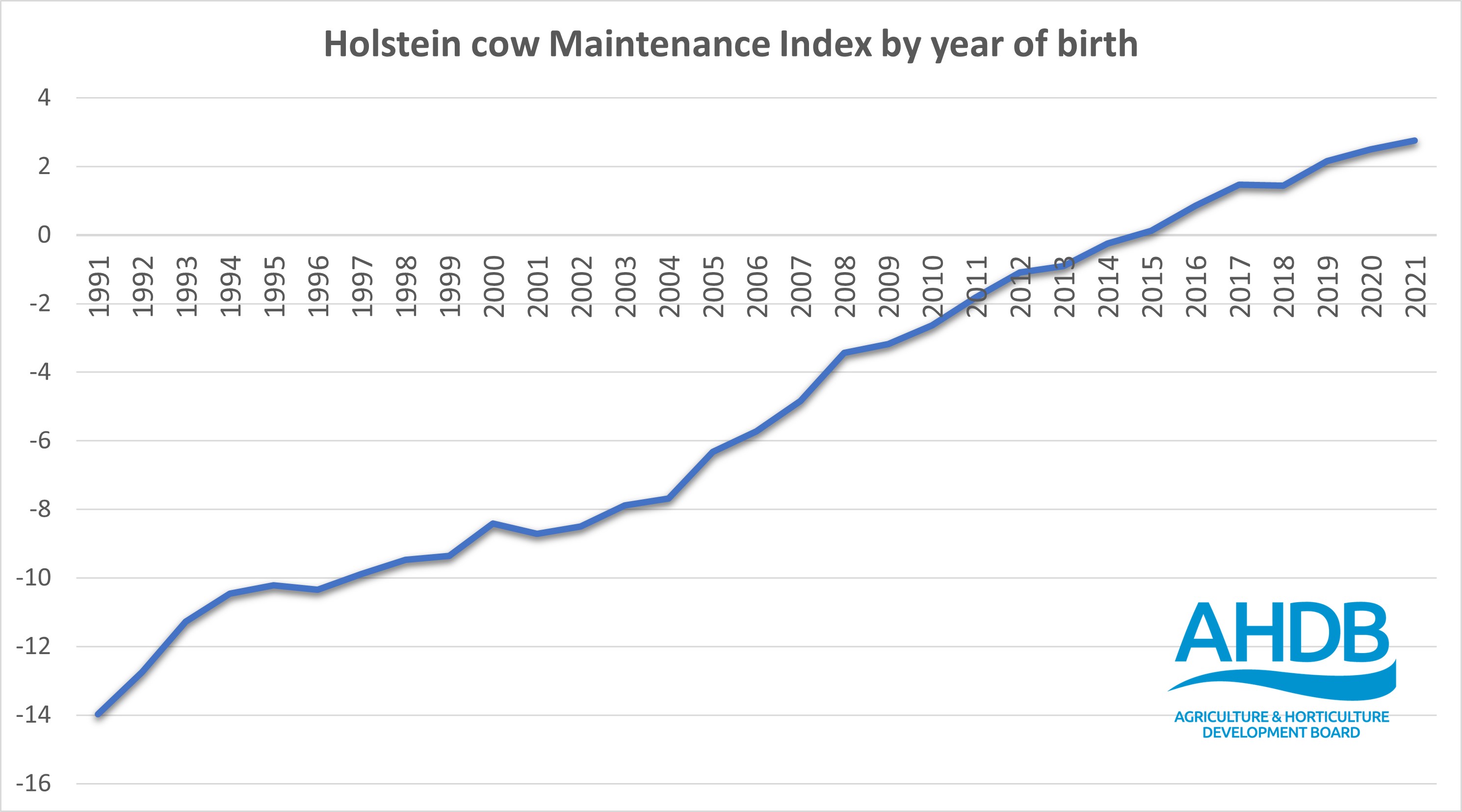

“AHDB’s Maintenance Index – a genetic score for liveweight, and hence, the maintenance feed costs of keeping a cow – has been included in £PLI since 2014,” he says. “All other things being equal, it is always better to use a bull which has a lower Maintenance Index and therefore transmits lower maintenance feed costs to his daughters.”

However, despite its introduction around eight years ago, Maintenance Index continues to rise across the national herd (see graph 1).

“Over the past 30 years Maintenance Index has risen by at least 15 points, translating to a 30kg genetic difference in the average weight of a cow in 2021 compared with a cow in 1991,” he says.

This extra bodyweight means the average, 200-head, UK herd is feeding an extra 10 cows every day, just for the sake of having bigger cows!

Back in the Huddlestone herd, Keith Gue is carefully watching the outcomes in his cows and heifers as he continues to push liveweight downwards.

He says: “We know our efficiency is going up as we measure our dry matter of feed consumed every month and the weight of energy-corrected milk we ship, and this ratio is improving as a general trend all of the time.”

Furthermore, the herd’s average production sits at 12,082kg at 4.27% fat and 3.45% protein; it has more VG 2yr heifers with every classification and amongst its 420 head, there’s a total of over 100 Excellent classified cows.

“Huddlestone, along with several other leading herds in the UK, dispel the myth that you need to breed for tall, wide cows to have a great looking herd,” remarks Marco Winters.

“For other producers who have not yet started to reduce the size of their Holstein cows, I would urge them to do so by using zero or negative stature and Maintenance Index bulls.

“The herds with smaller, more efficient cows will have ease of management, a lower carbon footprint, be nimble in the face of difficult economic conditions and have the best chances of survival into the future – just like the cows themselves!”