How can trade flows affect primary production long term?

Thursday, 8 August 2019

Recently published articles have examined the potential impact issues such as tariffs/non-tariff measures (NTMs) could have on the beef and sheep industry, following on from a report compiled by The Andersons Centre. However, those were short-term estimates of the impact on prices. How the industry will react will be the biggest game changer.

The current landscape

It will come as no surprise that the EU is a key partner when it comes to beef and sheep trade. Circa 90% of beef exported from the UK goes to the EU (and vice-versa) whilst around 95% of UK sheep meat exports go to the EU. For sheep meat imports, non-EU countries are more crucial with nearly 90% coming from New Zealand (NZ) and Australia (Aus). Under the current agreements, we have free trade with the EU and preferential trade with NZ & Aus. Therefore, if Brexit is cancelled there should not be any additional impact from trade. Although if this was the case then the EU-Mercosur trade deal would apply, a conversation for another day.

A Brexit deal is agreed

Arguably the hardest option to predict given the previous “Brexit day” extensions and current political landscape. There is no clear indication that talks between Boris Johnson and the EU will occur or what sort of deal may be drafted (as of 7 August).

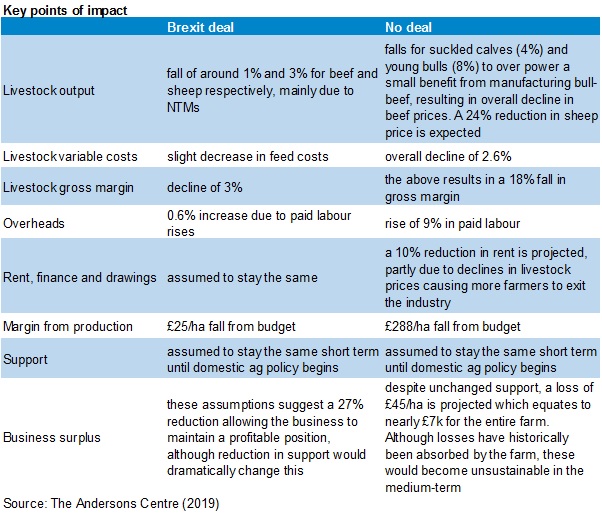

Therefore, if we assume a Brexit deal will include some sort of free trade agreement it is likely to see little disruption to trade. However, trade friction would have increased, which could exert upward pressure on prices depending on how these costs are accounted for in the supply chain. While in theory upward price pressure is a good thing, consumption of beef and sheep (the latter especially) is far behind pig meat and poultry. Depending on the impact of tariffs and NTMs on beef and sheep meat, there is a risk of further switching to poultry and pork if prices increase.

The future relationship between the UK and EU would therefore be key, as well as any trade deals with the likes of NZ & Aus, to any reduction in trade friction. Although a crucial part of price shaping, market forces and domestic policy will be the largest influencers of changes to primary production.

No deal Brexit

The following analysis has been done based on the UK’s proposed tariffs published in March 19 (in the event of no deal). Mr Johnson’s regime could change them.

Under no deal, the analysis suggests that UK consumption of beef and sheep is expected to rise 8.6%. However, this would be due to price falls.

For beef, this would be driven by increased competition from global imports, largely displacing imports from the EU at lower costs and thus reducing the overall value in the UK market.

The situation is slightly different for sheep as the increased barriers to export to the EU would see more domestic production on the market. In terms of trade volumes, we import and export about the same amount, however, carcass balance becomes a problem. For example, shoulders are not in huge demand in the UK whereas legs are. Therefore, the increased domestic supply, of product not in demand, will bring prices down.

Farm impact

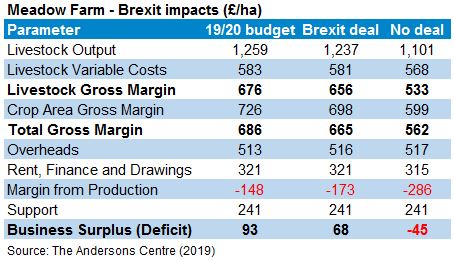

Andersons’ Meadow Farm Model* has been used to assess what all this could mean for primary production.

Overall, the results show the significant negative impact a no deal Brexit could have to a livestock farmer. The results above are short-term impacts of the tariffs and NTMs but do not take into account how farmers will react to these. Regardless of what happens with support payments, a number of livestock (mainly sheep) businesses will not be able to survive long-term without significant changes in their business model. This could be a change to the farming system and/or diversification. However, those will not be options for everyone and a no deal Brexit could result in some farmers having to leave the industry or scale back in order to have additional income sources (i.e. off-farm income).

It is, therefore, paramount to keep up to date with latest developments around support payments, especially the revamped environmental schemes. As well as this, there a number of ways farmers could mitigate some of the impacts this, or any, situation may cause. Focusing on what can be controlled is crucial to this and more information can be found on the AHDB website, in the Preparing for Change: The Characteristics of Top Performing Farms report and webinar.

* Andersons’ ‘Meadow Farm’ is a notional 154-hectare (380 acre) beef and sheep holding in the English Midlands. Of this, 114 Ha is owned, and the remaining 40ha is rented via a Farm-Business Tenancy (FBT). The farm consists mostly of grassland, with some wheat (13ha) and barley (16ha) grown mainly for livestock feed. There is a 60-cow spring-calving suckler herd with all progeny being finished, a dairy bull beef enterprise (35 animals) and a 500-ewe breeding flock. It is run by the proprietor and employs one full-time family worker as well as casual labour during peak periods (e.g. lambing season).

The farm is run on a real-time basis by Andersons’ Farm Business Consultancy department and is based on the trends witnessed at farm level; however, it is not based on any particular farm’s data. Whilst this is a ‘model’ farm, it is not considered to be a model (benchmark) in terms of performance. It is significantly behind the top-performing livestock farms; however, it is reflective of an average grazing livestock farm across England and the UK generally. Therefore, it offers useful insights on how the impact of Brexit could affect beef and sheep farmers generally.