- Home

- Does the SFI provide a good economic alternative to break crops?

Does the SFI provide a good economic alternative to break crops?

Finding a reliable break crop in the arable rotation is an ongoing challenge. Could Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) actions, such as herbal leys or legume fallows, act as a favourable alternative? This article examines scenarios where winter oilseed rape and winter beans are replaced with SFI actions of a herbal ley or a legume fallow.

Key messages

- From a financial perspective, it is only worth replacing break crops with an SFI action of planting a herbal ley or legume fallow if they are prone to consistent crop failure

- Only replace break crops with herbal leys or legume fallows when they can be established fairly easily and have a positive effect on the wider farm

- Do not make decisions based on circumstances in one isolated year: an SFI agreement is for three years, so it is important to take a multi-year approach

- Price volatility is an inherent feature of agricultural commodity markets – the SFI can act as a stable component of farm business income and will be especially important under challenging market conditions

A new and improved SFI in 2024?

This year the SFI appears to be moving in the right direction for some farmers. It offers:

- Fifty new actions for farmers to choose from summer 2024

- Flexibility to tweak agreements annually

- Improved payment rates

We have carried out analysis looking at how much money farms could receive by stacking various SFI actions. While the SFI will not replace the income received from direct payments, if planned carefully it can provide considerable income for farm businesses. Improvement in net profit (total revenue minus total costs) of the farm business is most likely when land is not taken out of production.

However, this may not always be the case. Poor prices, coupled with the challenges farmers face in growing break crops such as oilseed rape, have led to the question, “would it be worth establishing a herbal ley or legume fallow in the rotation instead?”.

This article examines various scenarios where winter oilseed rape and winter beans are replaced with SFI actions of a herbal ley or a legume fallow.

Methodology

This analysis is carried out using the 455 ha arable AHDB virtual farm, located in the East of England. The virtual farms are theoretical farms that exist on a spreadsheet. They are designed to be representative of ‘typical farms’, fitting within the middle-, 50%-performing businesses.

Find out more about the 455 ha arable virtual farm.

Note that the 2023 baseline is used as it is the most recent year with a full set of data.

An SFI agreement runs for three years, so we have looked at the effect on the farm’s net profit for each of these years.

Overall, the net profit of the farm falls over the three years; this is due to progressive reductions in direct payments. All other variables, such as prices and yields, were kept constant over the three-year duration – this allows us to measure only the effect of replacing rapeseed with an SFI action.

Winter rapeseed

The 455 ha arable virtual farm has 31.5 ha of winter rapeseed in its rotation. This analysis examined the effect on the farm’s net profit if the area used to grow winter rapeseed is used instead for an SFI herbal ley (SAM3) or legume fallow (NUM3) action.

Three scenarios have been examined, which are listed below. The price is constant in each scenario, but the yield varies. The third scenario is one where the entire rapeseed crop fails.

- Scenario 1 – average rapeseed yield of 3.28 t/ha, price of £413/t

- Scenario 2 – below average rapeseed yield of 1.5 t/ha, price of £413/t

- Scenario 3 – rapeseed crop failure

Note: The average yield uses data from Eastern England (2014–2023)

In all three scenarios, the overall payment the farm receives from the legume fallow (SFI NUM3) is greater than that from the herbal ley (SFI SAM3). This is due to both the higher payment rate per hectare plus the lower relative cost of carrying out this action.

If the herbal ley was kept on the same parcel of land for the duration of the three-year agreement, the farm would receive a higher net payment in years 2 and 3 because there would be no establishment costs. However, if the herbal ley was part of the farm’s rotation (which one would expect if it was to replace rapeseed), then it would need to be established each year of the agreement and so incur additional costs.

In this analysis, it is assumed that the herbal ley is carried out as a rotational action. If it was treated as a static rotation and carried out on the same area of land for the duration of the SFI agreement, this would ultimately reduce the area available for crop rotation. Our previous analysis shows that this would have an overall detrimental effect on the farm’s net profit.

From an environmental perspective, the longer the herbal ley is present on a piece of farmland, the greater the benefit. It can take up to four years for improvements to soil structure and fertility.

Scenario 1

Scenario 1 compares the effect on the farm's net profit if 31.5 ha farmland was used to grow:

- Average-yielding winter rapeseed

- Herbal ley (SFI SAM3) or a legume fallow (SFI NUM3)

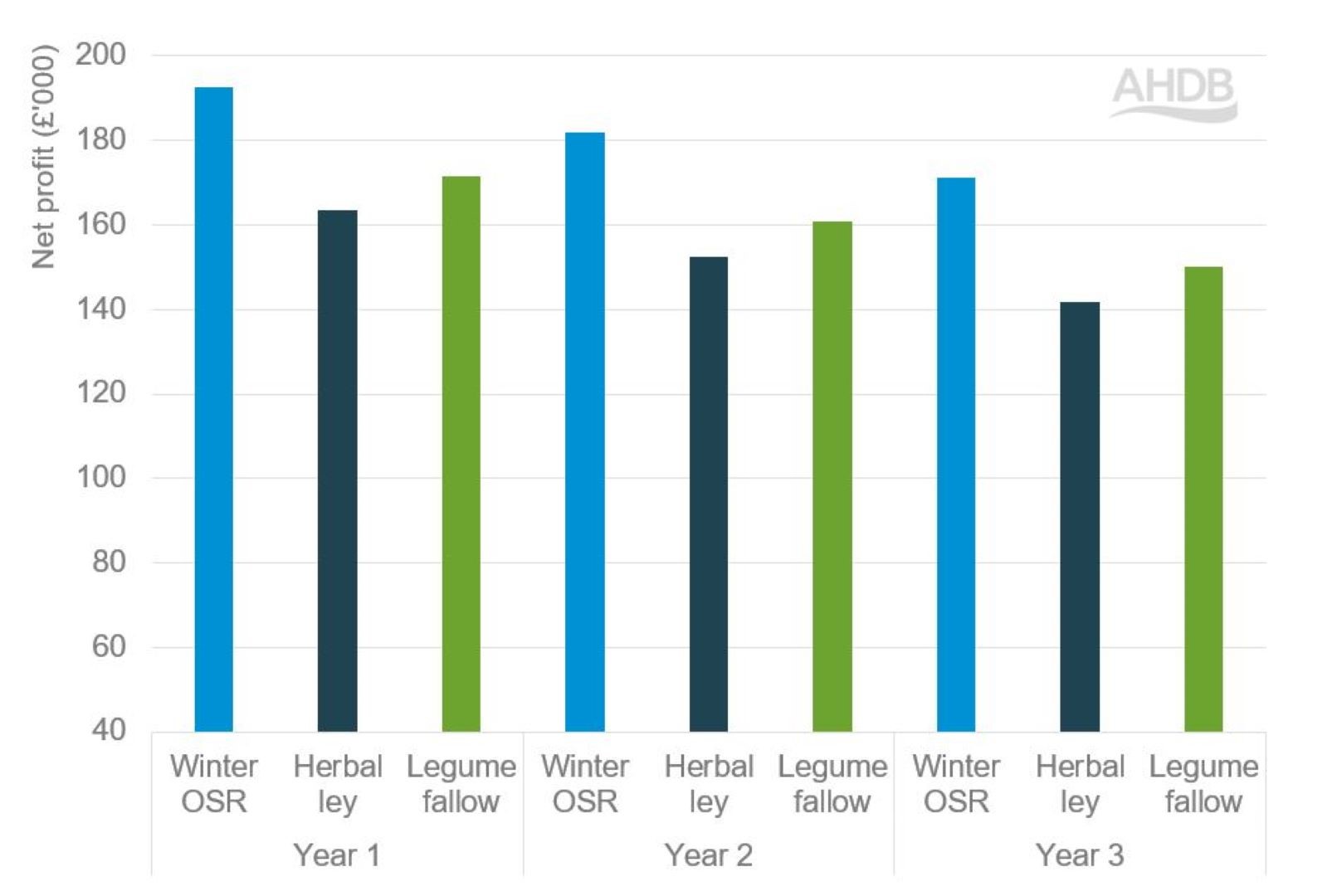

Figure 1 examines how the net profit of the farm would vary each year of the SFI agreement in this scenario.

Figure 1. Comparison of net profit between average-yielding rapeseed (Scenario 1), herbal ley (SFI action SAM3) and legume fallow (SFI action NUM3) on 455 ha virtual arable farm

In all three years of the agreement, the net profit of the farm is the highest when average-yielding winter rapeseed is grown (Scenario 1). The legume fallow is the next best option out of the three choices shown − herbal ley is the least profitable decision.

Scenario 2

Scenario 2 compares the effect on the farm's net profit if 31.5 ha of farmland was used to grow:

- Below-average-yielding winter rapeseed

- Herbal ley (SFI SAM3) or a legume fallow (SFI NUM3)

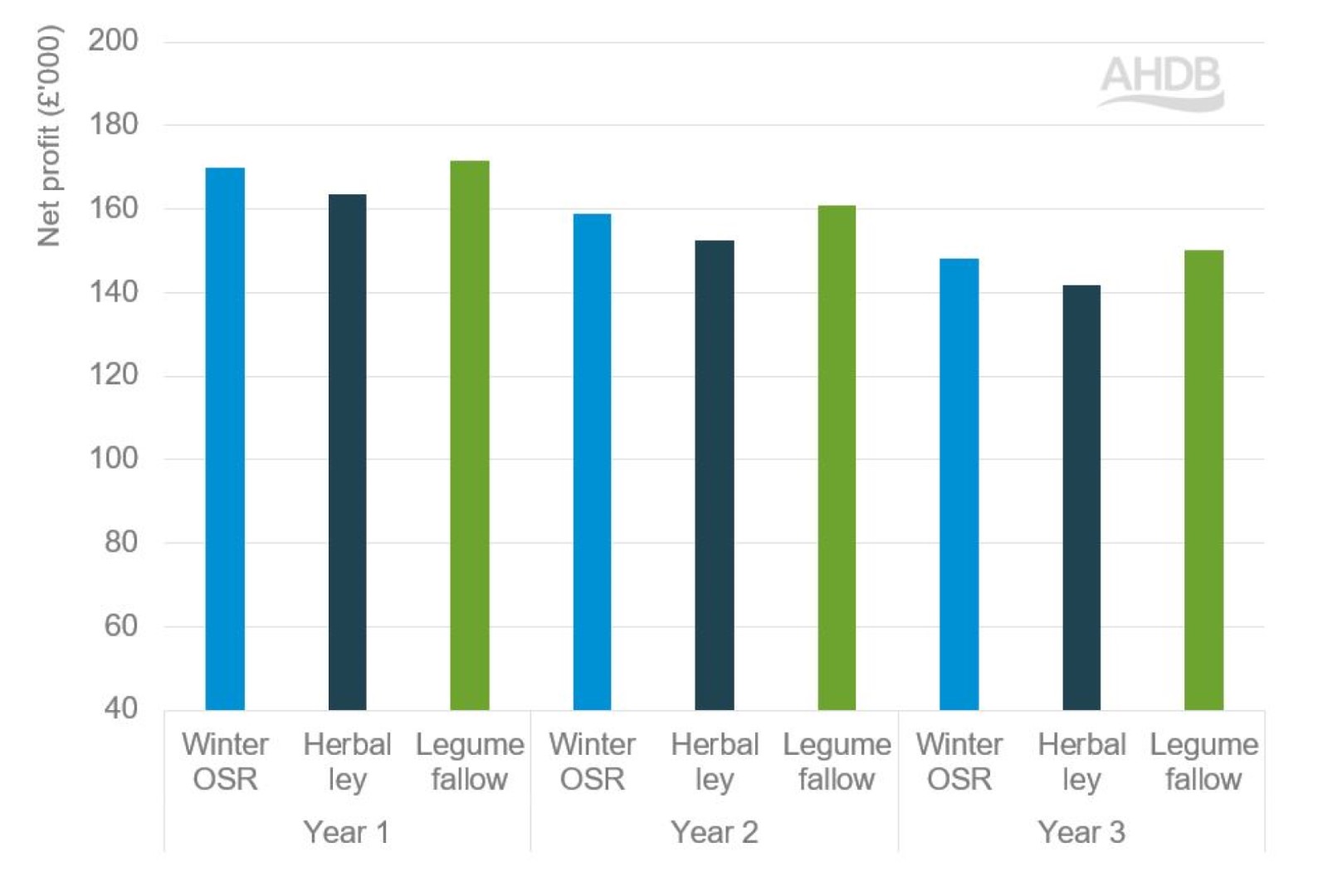

Figure 2. Comparison of net profit between below-average-yielding rapeseed (Scenario 2), herbal ley (SFI action SAM3) and legume fallow (SFI action NUM3) on 455 ha virtual arable farm

Under Scenario 2, the net profit of the arable farm is highest with an SFI legume fallow. However, the increase is rather modest, at around 1%. If an SFI herbal ley was grown instead of winter rapeseed, the net profit of the farm would be around 4% lower.

Scenario 3

Scenario 3 compares the effect on the farm's net profit if 31.5 ha of farmland was used to grow:

- Failed winter rapeseed crop

- Herbal ley (SFI SAM3) or a legume fallow (SFI NUM3)

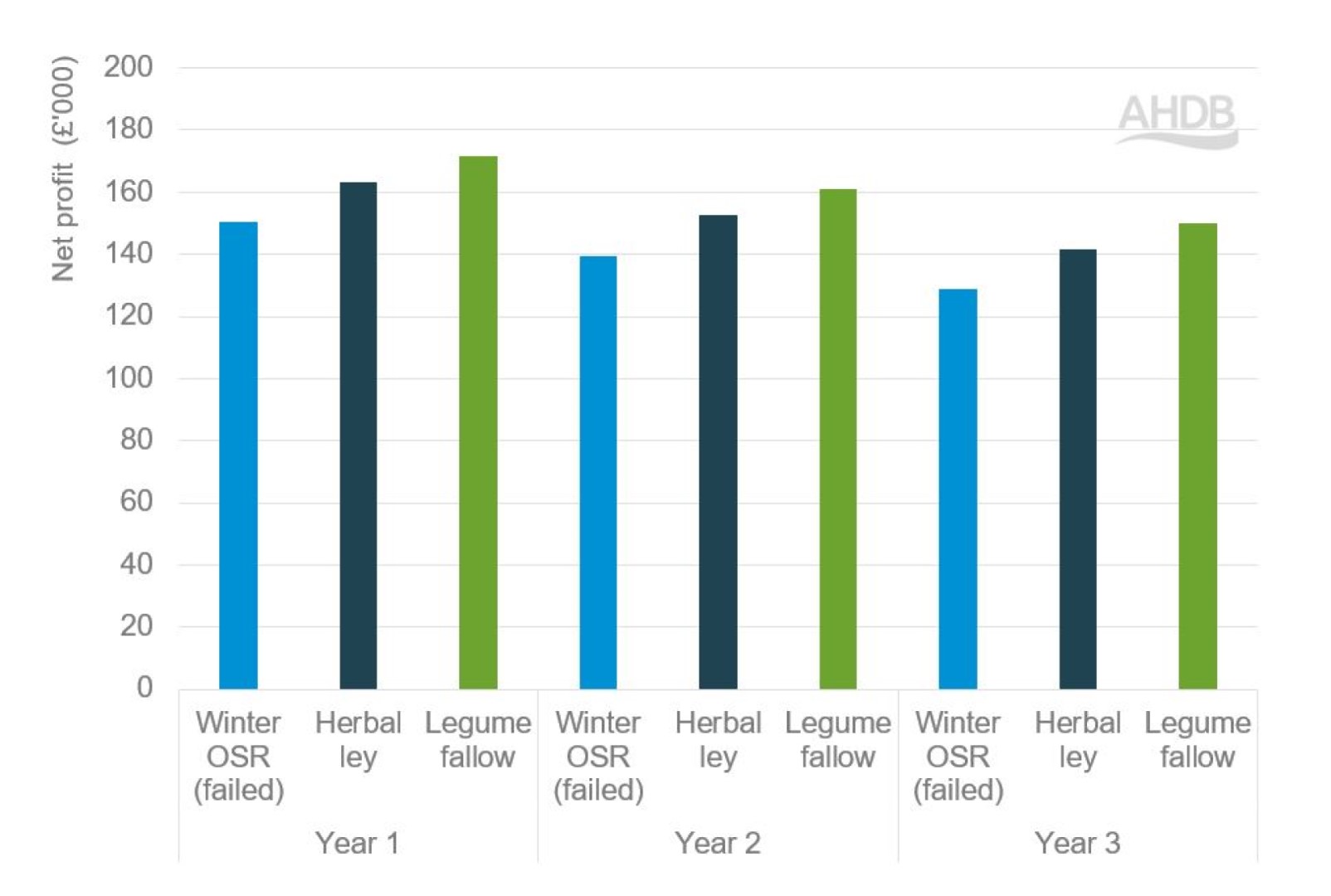

In the event of a failed rapeseed crop, there is no doubt that the SFI legume fallow or herbal ley would be considerably better alternatives, as they would at least provide the farm with some income.

Figure 3. Comparison of net profit between rapeseed crop failure (Scenario 3), herbal ley (SFI action SAM3) and legume fallow (SFI action NUM3) on 455 ha virtual arable farm

Figure 3 shows that the net profit of the arable farm would be around 9−10% higher if an SFI herbal ley replaced winter rapeseed over the three years. If an SFI legume fallow was grown instead, the net profit would be around 14−17% higher.

Winter beans

The 455 ha arable farm has 36 ha of winter beans in the rotation. As for winter rapeseed, we have looked at the effect on the farm’s net profit if the 36 ha area used to grow winter beans is instead used for an SFI herbal ley (SAM3) or legume fallow (NUM3) action.

The three scenarios listed below have been examined – the price is constant in each scenario but the yield varies. The third scenario encapsulates the situation where the entire winter beans crop fails.

- Scenario 1 – winter beans yield of 3.68 t/ha, price of £211/t

- Scenario 2 – winter beans yield of 1.8 t/ha, price of £211/t

- Scenario 3 – winter beans crop failure

Scenario 1

Scenario 1 compares the effect on the farm's net profit if 36 ha of farmland was used to grow:

- Winter beans with a yield of 3.68 t/ha

- Herbal ley (SFI SAM3) or a legume fallow (SFI NUM3)

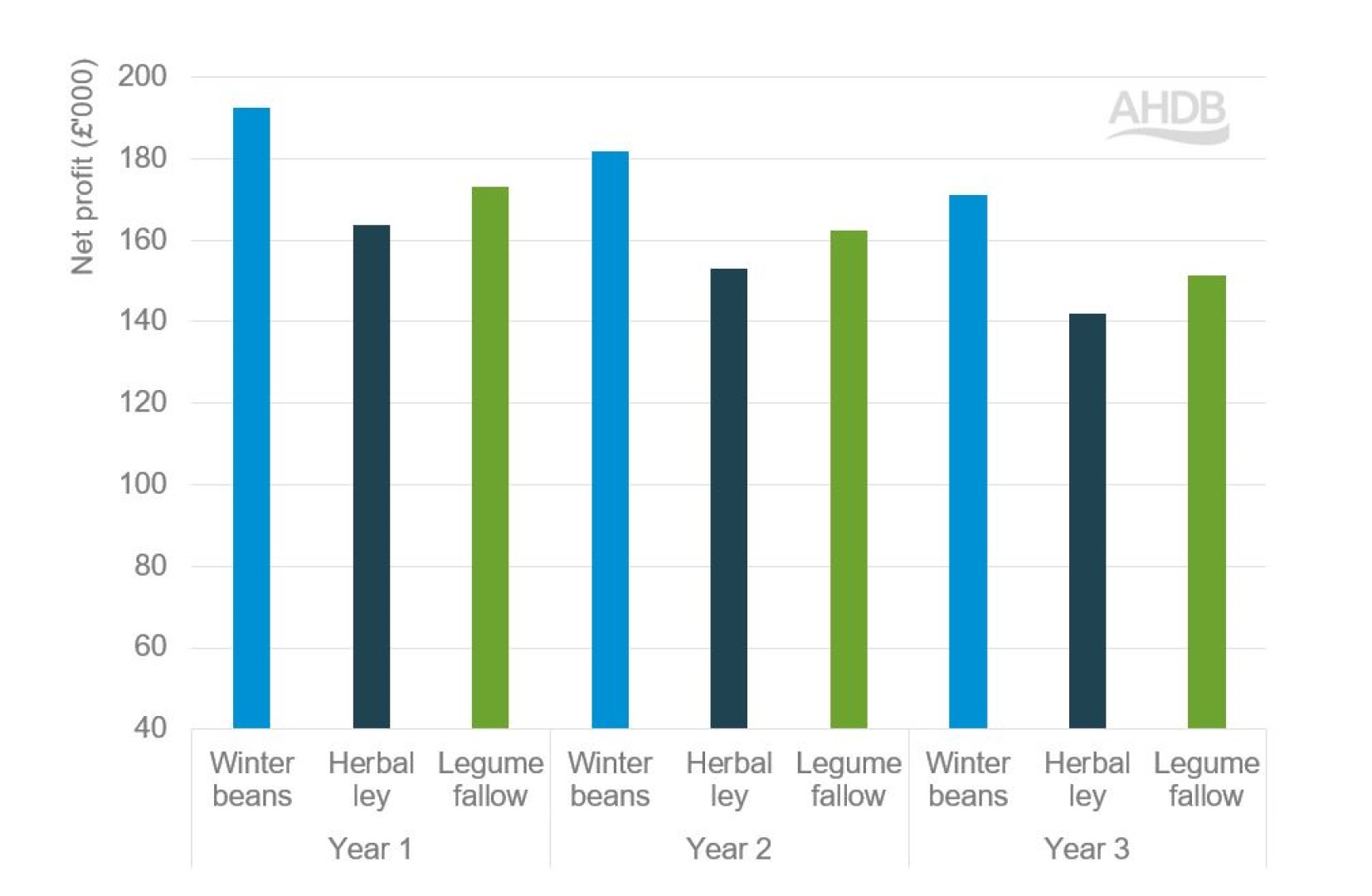

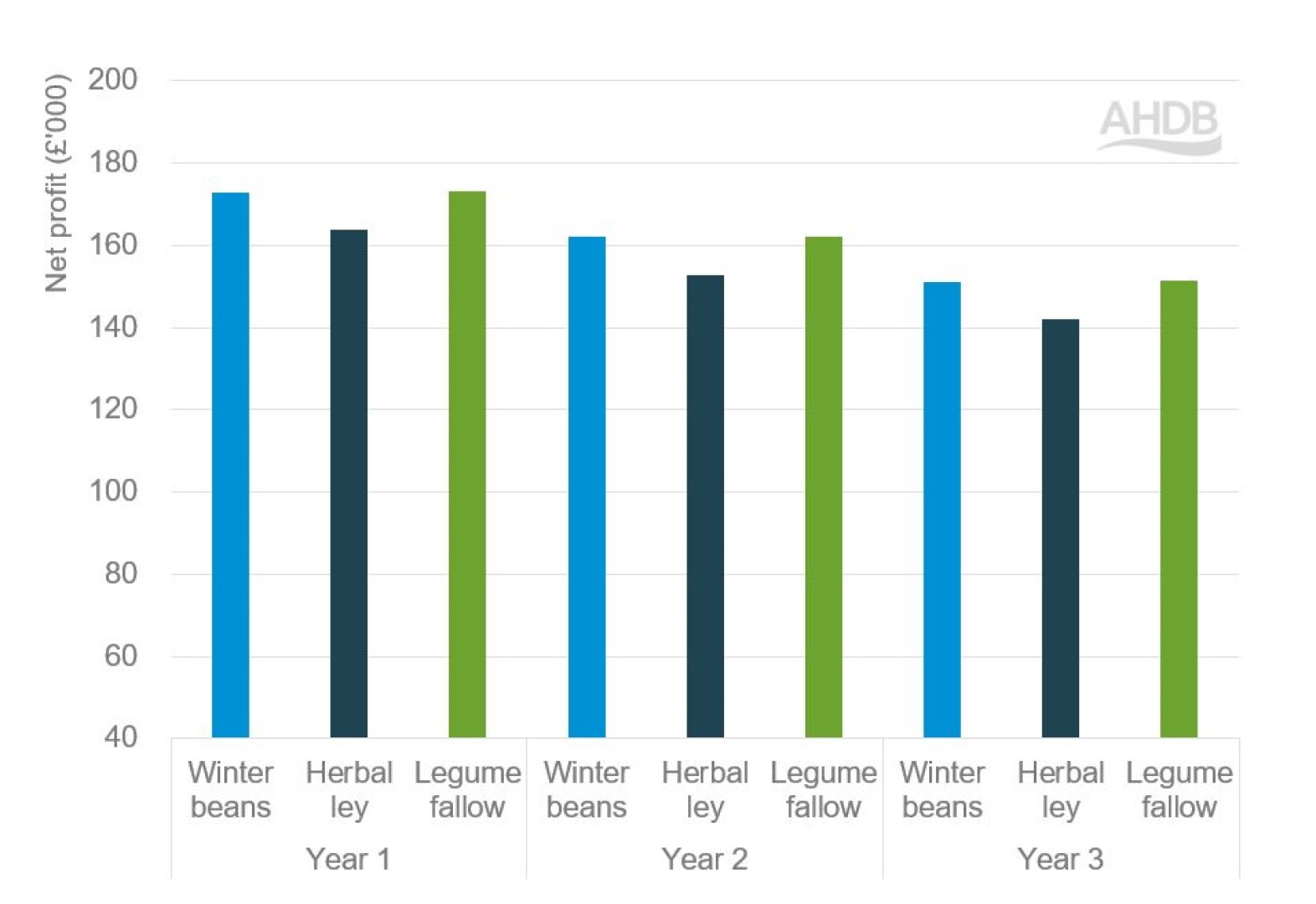

Figure 4. Comparison of net profit between winter beans (Scenario 1), herbal ley (SFI action SAM3) and legume fallow (SFI action NUM3) on 455 ha virtual arable farm

Figure 4 shows that replacing a winter beans crop with either SFI herbal ley or legume fallow would reduce the net profit of the farm. In this scenario, keeping winter beans in the rotation is the best option for the farm in terms of obtaining the highest net profit.

Scenario 2

Scenario 2 compares the effect on the farm's net profit if 36 ha of farmland was used to grow:

- Winter beans with a yield of 1.8t/ha

- Herbal ley (SFI SAM3) or a legume fallow (SFI NUM3)

Figure 5. Comparison of net profit between winter beans (Scenario 2), herbal ley (SFI action SAM3) and legume fallow (SFI action NUM3) on 455 ha virtual arable farm

As seen in Figure 5, replacing a winter bean crop with an SFI legume fallow makes a negligible difference to the 455 ha arable farm’s net profit. Replacing winter beans with an SFI herbal ley would result in a 5−6% decline in the farm’s net profit.

Scenario 3

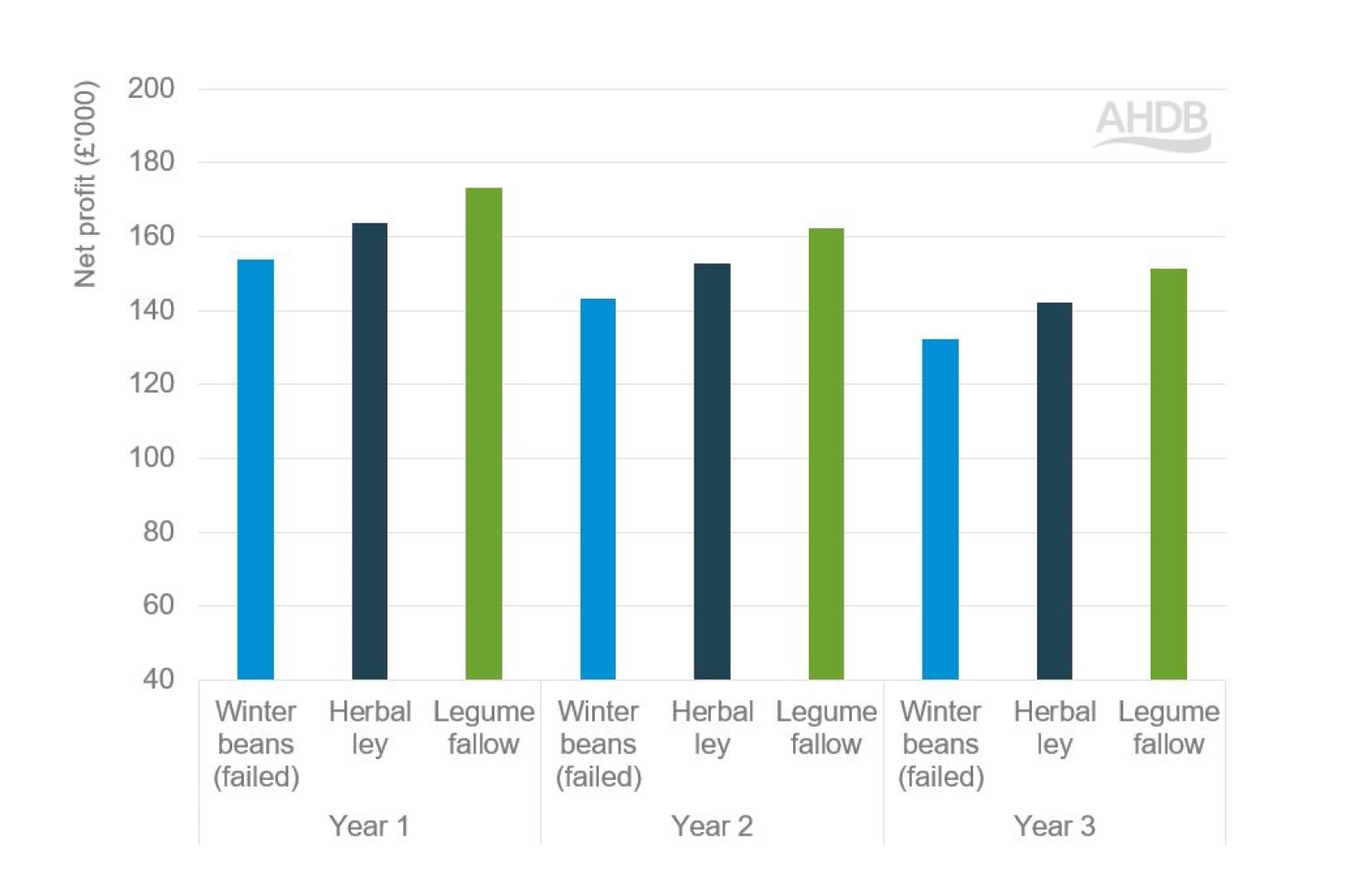

Scenario 3 compares the effect on the farm's net profit if 36 ha of farmland was used to grow:

- Failed winter beans crop

- Herbal ley (SFI SAM3) or a legume fallow (SFI NUM3)

Figure 6. Comparison of net profit between winter beans crop failure (Scenario 3), herbal ley (SFI action SAM3) and legume fallow (SFI action NUM3) on 455 ha virtual arable farm

Unsurprisingly, as an alternative to a failed winter beans crop, both SFI herbal ley and legume fallow are better options. The 455 ha arable farm’s net profit would be 6−7% better off with an SFI herbal ley compared with a failed winter beans crop and 12−14% better off with an SFI legume fallow (Figure 6).

Can livestock in rotation amplify revenue from herbal ley?

Figures 1−6 demonstrate that replacing either winter rapeseed or winter beans with an SFI legume fallow may be more favourable on the farm’s net profit compared with an SFI herbal ley. However, the SFI guidance states that legume fallow (NUM3) cannot be grazed by livestock, while there is no such restriction for a herbal ley (SAM3).

This difference invites the possibility of introducing livestock into the arable rotation, which could graze on the herbal ley; this may contribute further revenue to the arable farm.

It is important to note that this is not a straightforward action to take. For example, a livestock and arable farmer would need to consider what type of agreements would be best. It could mean changes in farm infrastructure and on the overall effect on the farm and livestock. If this is something you wish to explore, see AHDB’s work on livestock and the arable rotation.

Studies have shown that herbal leys could extend the grazing season and provide an improved feed for livestock. However, the grazing system should be carefully considered. Over grazing could damage the herbal ley; this would result in a reduction in associated yield and benefits. The type of stock should also be considered, as certain animals will target specific sward species leading to a reduced sward diversity.

If it turns out that livestock can be effectively introduced to your farm, the overall effect of replacing either winter rapeseed or winter beans with an SFI herbal ley is likely to be greater than that shown in Figures 1−6.

Introducing a herbal ley in the rotation could also be an efficient way to control black grass. Farm businesses with this challenge may benefit economically in the longer run from planting herbal leys.

Is it worth replacing break crops with SFI actions?

As the analysis shows, it depends. If your break crop consistently fails and offers little return, then SFI actions, such as a herbal ley or legume fallow, may offer a better alternative in terms of a source of ‘guaranteed’ income. However, this income depends on the successful establishment of a herbal ley and legume fallow.

Farmers will need to assess:

- Whether the land and soil is suitable

- How the composition of the herbal ley may affect other elements of their farm (e.g. grazing livestock)

- How it fits within the overall system of the farm

A benchmarking platform, such as Farmbench, can help farmers track their crop performance and support these types of management decisions.

An SFI agreement is for three years. While the area of land for rotational actions, such as a herbal ley or legume fallow, may be reduced, the new area entered into the scheme must be at least 50% of the original area entered. Any decision to replace crops with SFI actions needs to be taken with a multi-year view and understanding of the implications.

As stated in our SFI stacking analysis, the SFI can act as a buffer in challenging years − be that due to low market prices or poor crop growing conditions (or both). In good years, however (favourable yields, decent prices), the farm would not make as much with SFI actions compared with growing crops.

It largely depends on your viewpoint: is the aim to make as much money as much as possible, or lose as little as possible? For the latter approach, the SFI provides an option. However, this is purely from a short-term, economic perspective. If the aim is to increase the productivity of your land and soil, the economic benefits of herbal leys or legume fallows are likely to be reaped over a longer period.

Useful links

Food verses environment – the unintended consequences of the SFI

Livestock and the arable rotation