The long term arable market outlook

Friday, 29 January 2021

As part of this Agri-Market Outlook, we’re taking a longer-term view of the changes that may impact our agricultural sectors. In this article, David Eudall, Head of Arable Market Specialists, looks at what may influence the domestic arable sector in the coming years.

Considering all of the issues in 2020 from coronavirus and protracted EU trade deal negotiations, it feels that these outlooks are at a very pertinent point in time. Almost as if this is the year where the decade starts again and we have been waiting for the starting pistol to go off to allow us to proceed.

So how have the key long-term issues in arable markets developed over the past 6 months since our last outlooks?

Cereals and oilseeds

The biggest risk to cereals and oilseeds was no agreement on a trade deal with the EU. Now we have a deal we are seeing short-term issues with trade friction. In the coming months, despite disruption to businesses, these will be rectified and a new trading pattern will emerge.

Whilst we have not seen an immediate appreciable impact on the bottom line for farmers, we must not be complacent over the longer-term issues.

Firstly, from an English point of view we know that subsidies will be eroded from this year onwards. We should expect that subsidies now be turned off across all regions of the UK before being replaced with new environmental schemes.

This creates a challenge to 3-5 year business planning, but for the arable sector wheat is the redeeming feature of forward planning.

Wheat is the only agricultural commodity in the UK that has a liquid and transparent forward market. With current prices high we can again get complacent, but actually this provides the best opportunity to start planning for the rest of the decade.

Do you understand all the marketing options available to you? What is your risk appreciation? Does trading grain keep you up at night?

All of these questions will become even more important in the coming years as a farmers profit is opened up more and more to the volatility of global markets as the cushion of subsidy is removed.

Those who have the foresight to improve their skills now will be the beneficiaries in the years ahead. Using our independent market information is just one part of the equation, having as many sources of information and regularly talking to end-users and merchants of their requirements and market expectations is needed.

We have always said there is no “one size fits all” strategy to trading grain. So now is the time to find out what fits you best. As the decisions you take will be more important in the years ahead.

Potatoes

In the short-term there are two challenges for the potato sector. Firstly, achieving third country equivalence for seed potato exports into the EU. Secondly managing the impact of coronavirus lockdowns on demand and stocks.

Both of these short-term factors have the potential to exacerbate an already shrinking grower base for potatoes. If we lose market access to key trading partners, the economics of growing potatoes in parts of the country drastically turn unfavourable. The impact of limited trading conditions further impacting growers bottom lines also poses a risk.

So let us think longer term. In my previous long-term view, I discussed consolidation of the potato grower base. I’ll now put some figures on that.

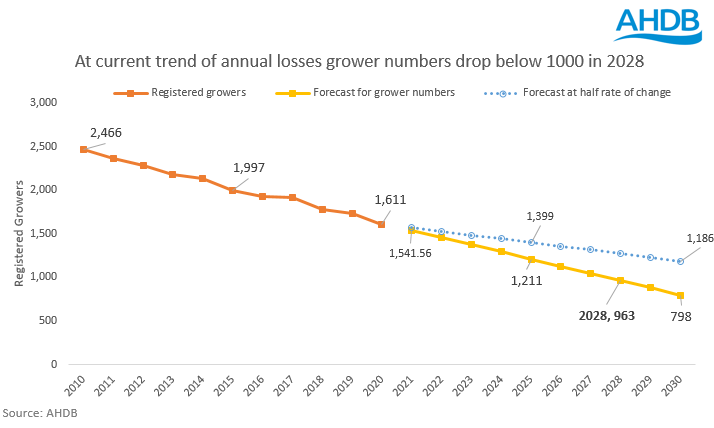

Our latest data for 2020 we see that grower numbers have taken a sharp reduction with 1,611 registered potato growers in GB (growing over 3 hectares). This comes in a year where area planted reduced by 2.7kha to 117.5kha. After the 3 years of weather and demand disruption, it is no surprise to see growers move away from potatoes as costs increase.

By 2030, potato growers will be less than half current levles if declines continue

Over the past decade, we have lost on average 81 growers per year, if the trend rate of decline since 2010 continues; we will be looking at a grower base of half current levels by 2030. Even at half the current rate of change we’d lose close to 500 further growers by the end of the decade.

To keep current production levels, that would require each grower to be producing potatoes from on average 147 hectares, which is nearly triple current levels (assuming yields unchanged at circa 46t/ha). Is there the scope to include this level of area change across rotations and regions? If we see a drop off in production in areas that have suffered in recent years (North-West England for example) can the rest of the country realistically increase area and production to offset this?

The latest cost of production estimates for 2020 show that since 2018 cost of production has increased by nearly 5% on a per hectare basis for fresh potatoes, and by 10% for processing potatoes.

So again, it is not surprise that growers are leaving the industry. Total area planted has also steadily been reducing; so does the industry face a longer-term challenge of cheaper imports from abroad coming into the UK as domestic supply security comes under pressure?

We are heading towards a vertically integrated supply chain with larger growers producing more on contract for specific end-markets. Could this efficiency be a good thing and help to drive a domestic provenance and sustainability for the future as supply chains share risk and reward, and increase collaboration to deliver a product that consumers demand?

Data holds the key to long-term arable success. Are we ready to embrace this?

Market failure occurs when there is imperfect market information. Inefficiency and costs increase as market participants make decisions based on incorrect, biased or monopolised data and information. The move to perfect market information would mean that all participants know all that is happening and there is full transparency.

There are risks at both ends of the information spectrum. From too little information creating bad decisions, or fully transparent information having an anti-competitive effect.

So where does the domestic arable market sit on this data scale, and what will the future hold for data development to reach the optimum point of clear market data to prevent market failure?

Firstly, let us celebrate what we have. We already have a wealth of data being collected domestically, with on-farm records to satellite cropping data and one of, if not the, longest running cereal price series in the world and much, much more.

Therefore, the question is not of revolution, but evolution. How do we combine and collect all this value into something that all within the marketplace can use. Whilst also navigating the tricky conditions of security, validity and commercial sensitivity.

We also have to ensure that the data produced is understandable, but also valuable enough to create an action for the user to improve their business performance in some way.

One of the key challenges we face is modernising data collection methods amid new technology. Gone are the days of physical inspections of crops, with satellites and drones increasingly becoming the go-to method.

However, this development needs to continue across all spectrums and adopted by those providing the data. Large volumes of information remains collected in a paper format. Not only does this pose an inefficiency in slow collection, it also prevents uptake as it takes time and effort to collect. A move to a more modern data capture methodology across the board will allow for speed of data, and therefore speed of decision.

In a marketplace for all commodities, that is becoming a more rapid, globalised marketplace, speed of awareness of issues, and remedies, will see the most proactive gain.

For potatoes, AHDB are one, if not the only, source of domestic market information. Expanding this to cover more detail across pricing of contracts and by sector will allow both growers to understand the marketplace, but also help inform supply chains and government of extreme market conditions such as the impact of coronavirus in the past 12 months.

None of this is simple or easy. There remains many hurdles to cross which we can deliver through improved engagement and awareness of data capabilities.

If this process is not a collaborative effort across all supply chains, then we still face the risk of market failure through imperfect information. Where those who are more able modernise internal systems to gain an advantage and create an imbalance of information in the marketplace.

This will be the decade of data. AHDB can be a central point to collate this data and provide impartial evidence to all in the industry for a positive change.

Sign up for regular updates

You can subscribe to receive Grain Market Daily straight to your inbox. Simply fill in your contact details on our online form and select the information you wish to receive.

While AHDB seeks to ensure that the information contained on this webpage is accurate at the time of publication, no warranty is given in respect of the information and data provided. You are responsible for how you use the information. To the maximum extent permitted by law, AHDB accepts no liability for loss, damage or injury howsoever caused or suffered (including that caused by negligence) directly or indirectly in relation to the information or data provided in this publication.

All intellectual property rights in the information and data on this webpage belong to or are licensed by AHDB. You are authorised to use such information for your internal business purposes only and you must not provide this information to any other third parties, including further publication of the information, or for commercial gain in any way whatsoever without the prior written permission of AHDB for each third party disclosure, publication or commercial arrangement. For more information, please see our Terms of Use and Privacy Notice or contact the Director of Corporate Affairs at info@ahdb.org.uk © Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board. All rights reserved.

Sectors: