A and B milk pricing: all you need to know

Changes to your pricing model will influence how much milk you produce, both in the short and longer term.

Back to Coronavirus: support for dairy farmers

How does A and B milk pricing work?

A and B pricing for milk has been around for a number of years, and was initially used to take some of the seasonality out of milk production. In recent years, however, processors are using A and B pricing as a way to balance milk supplies to market demand.

These pricing models typically set a limit on the volume of milk delivered (‘A’ volumes) and how it is delivered over the year. Typically, these volumes will be based on requirements to service its core customer base.

Any milk delivered in excess of the ‘A’ volumes is classified as ‘B’ volumes. Shortfalls in production may also be paid as ‘B’ volumes in some cases, depending on how the milk buyer has set up the scheme.

Many milk buyers have introduced or adjusted A and B pricing models to help deal with the current supply-demand imbalance in dairy markets. This pricing model allows milk buyers to use an ‘artificial’ quota to match milk purchases to core market needs. This reduces or eliminates the uncertainty over market returns on any surplus milk volumes (‘B’ volumes).

In an oversupplied market, the aim is to separate out the volumes exposed to lower returns on commodity markets and send a strong price signal to farmers, in a bid to incentivise lower milk production.

How are A and B prices set?

The price paid on the ‘A’ volumes is usually set in advance and is generally linked to returns achieved from the processor’s core markets. Because returns from these markets are often more stable and predictable, the milk buyer has more certainty in setting the price paid to the farmer.

A different price is then paid for any excesses (or shortfalls) in production (‘B’ volumes). The ‘B’ price is typically set after the product is sold, based on either a published market indicator (i.e. AMPE or UK Milk Futures Equivalent, milkprices.com) or actual market returns. The actual benchmark that a processor uses to set its ‘B’ price will differ, depending on how it markets its surplus volumes, but could include:

- Spot milk price

- Bulk cream price

- Skim milk powder price

- Average market returns from all sales

The ‘B’ price may be higher or lower than the ‘A’ price, depending on whether the market is oversupplied or undersupplied. As ‘B’ prices are based on actual market returns, they are typically set in arrears.

| Oversupplied market | Undersupplied market | |

|---|---|---|

| Deliveries above ‘A’ volumes |

Processor sells ‘B’ volumes at discount |

Processor sells ‘B’ volumes at premium ‘B’ price higher than ‘A’ price |

| Deliveries below ‘A’ volumes |

Processor buys shortfall at discount |

Processor buys shortfall at premium ‘B’ price lower than ‘A’ price Possible penalty for shortfall |

Is your ‘B’ price following the market?

An increasing number of farmers are being asked to reduce production and, in some cases, are facing additional price cuts through the use of A and B pricing. This then leads to the question of whether the ‘B’ price they are paying is accurately reflecting the market value for milk.

AHDB has previously looked at the impact of spot milk prices on the wider market. The volume of milk being sold on the spot market is extremely small, and using it as a guide to ‘B’ prices is, therefore, difficult.

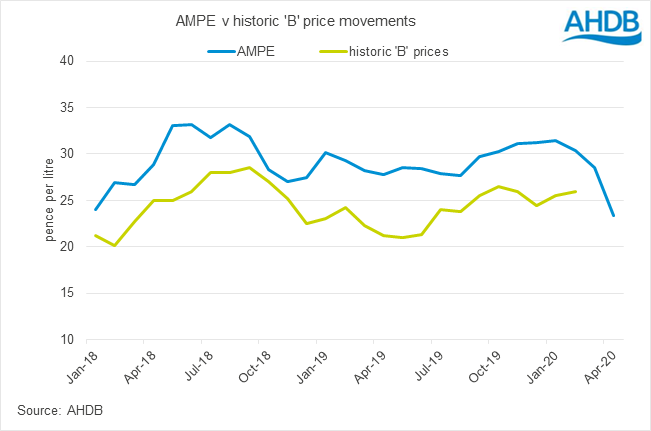

Of more relevance is whether ‘B’ prices are moving alongside commodity market prices. As any spare milk without a market or customer is typically converted into butter and skim milk powder (SMP), the returns on surplus milk should reflect movements in those markets. AHDB’s market indicator AMPE measures changes in returns for butter and SMP, and is, therefore, a good benchmark for assessing if ‘B’ prices are following the market.

In some cases, milk buyers will be basing ‘B’ prices on returns from other products, such as spot milk, bulk cream, skim milk concentrate or a combination of these products. While prices for these products may move at different rates and to different degrees in the short term, they will tend to follow similar trends over time. As such, movements in monthly ‘B’ prices should continue to track movements in AMPE.

AHDB would encourage any farmer on A and B pricing to engage with their processor, to understand how their ‘B’ price is being set and why it is where it is. Information on the ‘B’ prices paid by those processors included in the AHDB league table is tracked one month in arrears, and is available to download from our Milk price changes page.

Working with A and B milk pricing

A and B pricing models influence what farmers need to consider when making decisions on how much milk to produce, both in the short-term and longer term.

Short-term decisions will relate primarily to looking at what changes can be made to production levels to minimise or eliminate short-term losses associated with producing additional, or ‘B’, litres. However, it is important to do this without compromising the ability of your herd to produce milk when the situation changes.

In the longer term, farmers need to be mindful of the impact that changes to current volumes will have on their future ‘A’ allocations. This will depend on whether their buyer determines ‘A’ volume allocations from a fixed reference period or on a rolling basis.

With a fixed reference period, ‘A’ volumes are set as a percentage of a predetermined ‘base’ level of production. In this case, adjusting production to minimise unprofitable litres will not compromise future ‘A’ allocations, assuming the base period is not changed without consultation.

When core litres are determined on a ‘rolling’ basis, however, changes to production levels may affect a farmer’s future allocation of ‘A’ litres. For example, if ‘A’ volumes are set as a proportion of your average production over the past two years, reducing production this year to minimise unprofitable litres would reduce your ‘A’ allocation in future years.

The key for A and B pricing models to be successful is communication between buyers and sellers. This is essential, not only to better match supply to market demand, but also to ensure there is a mechanism in place for adjusting core volumes in a way that is not detrimental to the farmer.