- Home

- The dynamics of lameness prevalence

The dynamics of lameness prevalence

Whilst mobility scoring gives us a snapshot of how many cows are lame at the time; a single score doesn’t tell us what’s happening to that prevalence figure, according to Owen Atkinson.

If we simply make foot health for any individual cow, a binary measure – lame or not lame – hidden beneath that is whether the cow is getting better, worse, staying the same, or about to go lame.

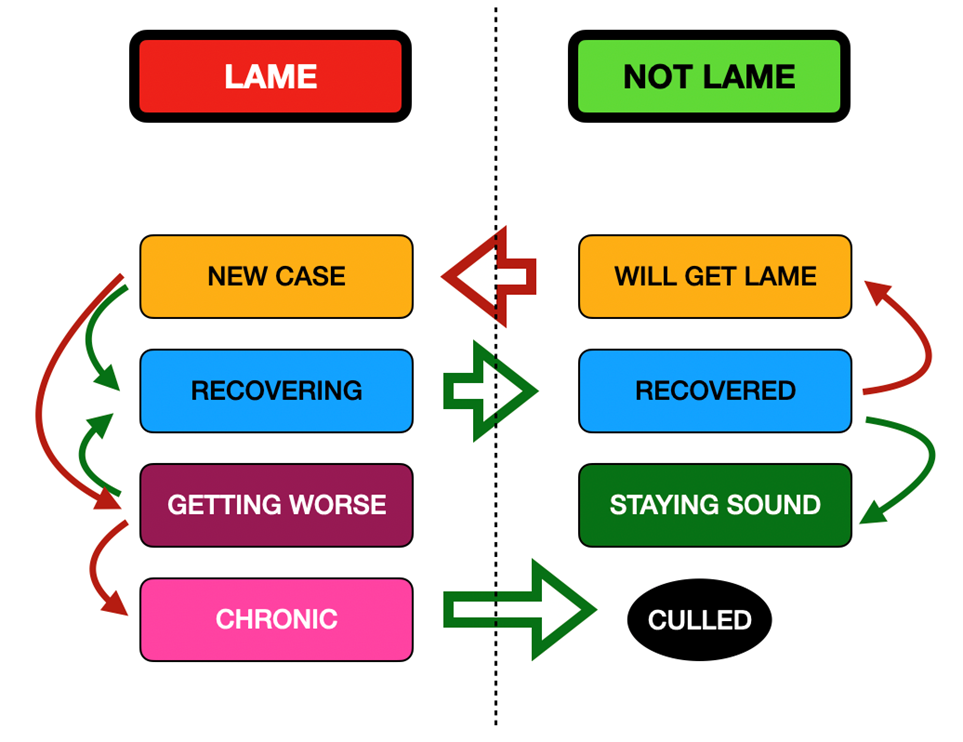

For example, an identified lame cow could be a new case and still to be treated, or she could have been treated and recovering, or she could be getting worse or staying the same (a chronic case). And for a non-lame cow, she could be recovered, forever sound, or just about to go lame. Figure 1 shows the different categories of lame and non-lame individuals and the dynamics between them.

Owen Atkinson

Owen Atkinson

Figure 1: Diagrammatic view of the dynamics of foot health category for individual lame cows.

Of course, the name of the game is to keep as many cows on the 'not lame' right-hand side of the dotted line.

The arrows show the potential movement of an individual between the various category of foot health. Movement represented by green arrows will tend to indicate an improving foot health scenario at a herd level (i.e. improving herd mobility scores), and the red arrows will tend to indicate a worsening of lameness prevalence.

It might not be rocket science, but in order to improve lameness prevalence for a herd, that will be via culling lame cows (usually the chronics) and/or improving treatment success rate, while simultaneously reducing the rate at which new cases are generated.

Many mobility mentors may have encountered a rapid reduction in lameness prevalence after their initial intervention – but if this is just because the farmer has culled his/her chronics without addressing underlying causes of new cases, the improvement will not be sustained. The other point to note is many cows appear to recover (apparent cures), but previous pathology (scarred digital cushion, new bone formation) means recovery is temporary. Hence the term 'apparent cure'. These cows with previous history are often the repeat offenders who quickly become the new chronics. So, it is important that a farmer understands what needs to happen to achieve a continuous and sustainable improvement in herd mobility scores. It can take a few years to see the full impact with healthy heifer cohorts calving in and staying healthy, eventually replacing the cows with existing, irreversible foot pathology. Monitoring parity 1 mobility score dynamics can be particularly helpful for this.

If only we knew which cows are in the 'will get lame' category. Nick Bell’s article in the next newsletter, Generating Trim Lists, discusses which cows to shed out for the trimmer and has some relevance here. To some extent, depending on farm type, a proportion of the 'will get lame' cows can be predicted and therefore targeted for a preventive trim. In housed, high-yielding herds, an early lactation trim to model the sole of the predominant weight-bearing claw (outer claw in back feet) might reduce the risk of lameness due to traumatic claw horn lesions (bruising and sole ulcers). Trimming long claws can similarly prevent a lameness event.

However, perhaps a more effective use of resources is to improve the recovery rates of the 'new case' category. This is done by adopting early detection and prompt, effective treatment (EDPET). Sara Pedersen has an article explaining more about that in this newsletter, and it is a vital piece of the jigsaw on all farm types, irrespective of the causes of lameness. For effective treatment, there is growing evidence that NSAIDs are beneficial for improving recovery rates and for reducing relapse rates. We would do well to promote the early and widespread use of NSAIDs for all types of lameness treatments, to augment corrective trimming and blocking for claw horn lesions, and rigorous topical treatment of digital dermatitis lesions.

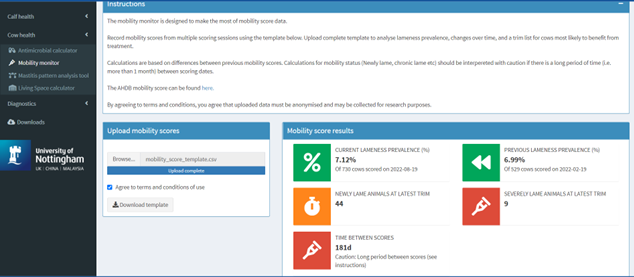

Ideally, as part of the Healthy Feet Programme, you will be able to track farms’ mobility data, so you can help farmers understand just how these lameness dynamics are playing out in their own herds. Some software can help you with this. Nottingham University Veterinary School have developed a free online tool which can help with some of this (https://herdhealth.shinyapps.io/toolkit/). Other commercial organisations have developed similar tools, e.g. NMR Mobility Monitor.

Owen Atkinson

Owen Atkinson

Figure 2 The Nottingham Mobility Monitor Tool.

Repeated scoring of individuals (maybe made easier by lameness scoring technologies in the future) allows a mobility mentor to calculate new case rates and recovery rates. If new case rates are high (the big red arrow in Figure 1), then attention should be refocussed on the underlying causes: go back to the Lameness Map of the Healthy Feet Programme and check that the most appropriate interventions were agreed in the action plan and that they are being implemented. If the new case rate is reasonable, but the recovery rate is poor (the big green arrow), attention should always be refocused on EDPET. Part of this should include a thorough review of how treatments and trimming are being done (see September 2022 MM Newsletter) as well as the promptness of detecting and acting upon the new cases. Anecdotally, many farms would benefit from more help here, and it is a dangerous assumption that treatments are resulting in good recovery rates.

In summary, take time to examine mobility data to check both new case rates and recovery rates. Be careful that a high culling rate does not mask an underlying failure to tackle the problems. Work with farms to help them understand what is happening within their own herds and to see what needs to be done to improve overall foot health.