- Home

- Fertiliser outlook

Fertiliser outlook

February 2026

Key points

- Fertiliser prices increased in 2025, a rise of 14% compared to 2024

- Usage and demand for fertiliser have remained stable

- The UK implementation of CBAM, plus further instability across Europe and the Middle East, could impact fertiliser prices through 2026

Over the last couple of years fertiliser prices have remained relatively stable compared to the volatility and huge spikes seen during 2022, which resulted from the energy crisis and changes in domestic supply of fertiliser.

Prices are still above pre-inflationary levels, however, and could be impacted by further global uncertainty and policy implementation.

See our March 2026 update following the outbreak of conflict in the Middle East

Demand for nitrogen fertilisers in GB

The latest annual British Survey of Fertiliser Practice report shows that total use of nitrogen across core products stayed stable in 2024. This was as expected as prices stayed consistent compared to previous years.

At field level, total nitrogen usage per hectare decreased by an average of 4 kg. This is mainly due to a decrease in straight nitrogen application: compound application rates remained in line with 2023 levels.

Around 82% of crops received a nitrogen application in 2024, the same amount as in 2023.

Use of urea and ammonium nitrate (AN) fertiliser have remained in line with usage in 2023, where we saw an increase in use of urea due to the structural changes in supply base.

Fertiliser prices

We publish GB fertiliser prices across seven fertiliser products every month, with the aim of increasing transparency in the market and helping levy payers understand the price trends.

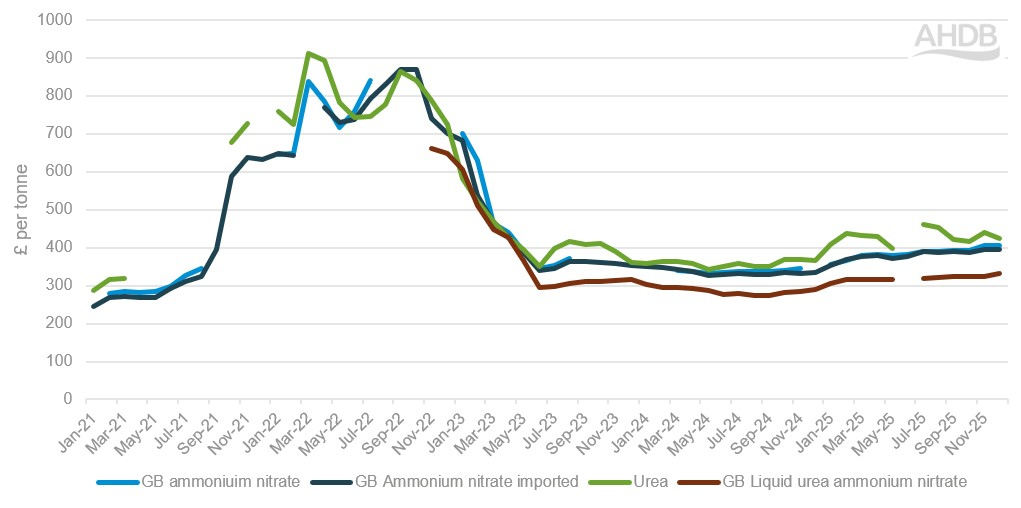

Nitrogen fertiliser prices increased in 2025 compared to 2024, up £50/t on average, about a 14% price increase. However, prices are still down £40/t compared to 2023, and down by 50% compared to the historic highs in 2022 (see Figure 1).

There is not much freely available information regarding fertiliser markets, unlike other agricultural commodities. This lack of information presents an issue for the resilience of food systems if we consider the turmoil in the markets that we saw through 2022 and 2023.

Figure 1. GB Fertiliser prices 2021-2025

Source: AHDB

The line graph at Figure 1 shows four categories of fertiliser: ammonium nitrate (blue line), ammonium nitrate imported (black line), urea (green line) and liquid urea ammonium nitrate (brown line).

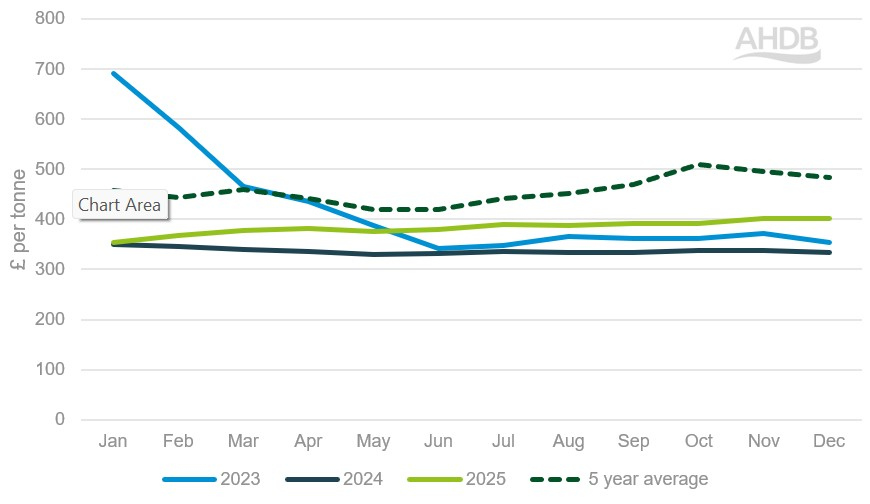

The line graph at Figure 2 below shows a closer look at ammonium nitrate fertiliser prices. Although 2025 prices were elevated compared to the end of 2023 and 2024, prices remained about £75/t below the 5-year average.

Figure 2 also shows that although prices have increased in 2025, these changes have been gradual and prices were relatively stable.

Figure 2. Ammonium nitrate fertiliser prices 2023-2025

Source: AHDB

What could impact fertiliser prices going forward?

Nitrogen fertiliser markets remained relatively consistent after the instability we saw in 2022 and early 2023.

Prices of GB fertilisers have remained stable over the last 24 months, and unless there are significant changes to the markets or global impacts markets, they will remain relatively calm over the next year.

Global instability will continue to present uncertainty in 2025, especially around supply of gas and shipping of fertiliser from the Middle East region. There are also ongoing uncertainties about natural gas due to the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Gas prices are a major driver for nitrogen fertiliser costs. It makes up 60-80% of the production costs; therefore any fluctuations in gas prices will have a knock-on impact.

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) was implemented in the EU on 1 January 2026, and is expected to be implemented in the UK on 1 January 2027. CBAM will place a carbon price on certain goods (including fertiliser) imported into the UK in emission-intensive industries.

In the EU, nitrogen fertiliser imports fell by more than 80% in January 2026, and prices are 25% higher than the 2024 average. More fertiliser was bought and imported in December 2025 in the EU in anticipation of CBAM being implemented.

The UK has reduced its reliance on EU fertiliser imports in recent years, due to a combination of high European gas costs and more competitive supply from the Middle East and the Americas.

The overall effect on GB farm fertiliser pricing in 2026 is expected to be modest, simply because the EU supplies a smaller share of the market.

However, the long-term direction is clear. Both the EU and UK CBAMs will increase the cost of high carbon fertilisers over time, making lower-carbon alternatives progressively more competitive as carbon pricing tightens.

For the UK, the main impact will apply from 2027 under the UK CBAM.

Fertiliser prices are impacted by global crop prices. Therefore if crop prices were to increase, this would allow fertiliser prices to follow if the markets have confidence in farmer demand. This is not a new risk, but something to consider when considering impacts to prices.

Going forward, although fertilisers have remained stable over the last couple of years, the increase in price during 2025 was felt more due to lower grain prices. Any fluctuation in input costs will ultimately affect cost of production and margins, especially when prices are lower.

Sign up to receive the latest information from AHDB