- Home

- Assessment of heat stress in dairy cows

Assessment of heat stress in dairy cows

During summer, heat stress is one of the factors that have the most significant negative impact on milk production, behaviour, health and welfare of dairy cows, especially in highly productive animals. The temperature–humidity index (THI) combines temperature and relative humidity to estimate the sensation of thermal (dis)comfort and is widely used to assess the impact of heat stress on dairy cows.

The Welfare Quality protocol has proved a useful tool for evaluating the welfare of dairy cows.

However, there is an essential gap regarding heat stress in the protocol, since an indicator for this aspect has not yet been included.

It is known that heat stress is influenced by a combination of different environmental factors (temperature, relative humidity, solar radiation, air movement and precipitation).

Temperature–humidity index (THI)

Several approaches have been proposed to measure the level of heat stress of animals. Most work has been done on THI, which combines temperature and relative humidity.

This index is affected by:

- Air velocity

- Radiation

- Posture and density of animals

- Production of heat

- The type of insulation of the housing

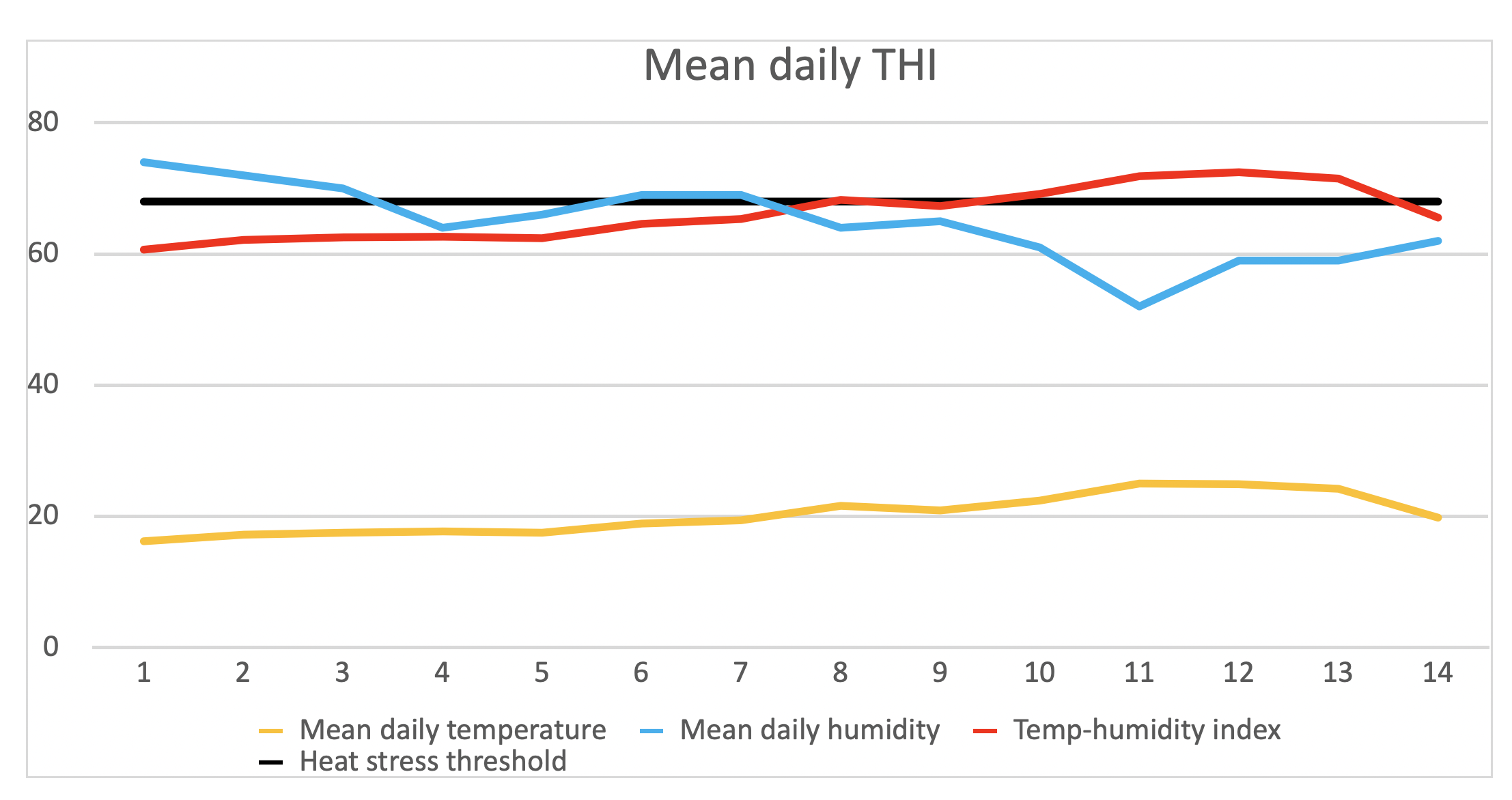

In temperate climates, the heat stress reduces daily milk production by 20% when THI values increase from 68 in spring to 78 in summer. Also, for each additional point in the THI values above 69, there is a decrease of 0.4 kg of milk per cow per day.

Although the THI could be a valuable addition in the Welfare Quality protocol, this protocol is mainly designed to be completed by welfare professionals.

To assist farmers in their day-to-day assessment and management of heat stress, there is a practical scoring approach for heat stress assessment using a scale based on behaviour and breath frequency (Table 1).

Table 1: Panting score using behaviour and breath frequency to quantify heat stress

| Description | Normal with no panting. | Slight panting, mouth closed with no salivation. | Fast panting with salivation present. No open mouth panting. | Open mouth panting and some drooling. Neck extended and head usually up. | Open mouth with tongue fully extended for prolonged periods and excessive drooling. Excessive salivation; usually with neck extended forward. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breaths per minute | <60 | 60–90 | 90–120 | 120–150 | >150 |

| Panting score | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Source: Mader et al., 2006

Case study – Dairy farm in Southern England

From local weather station data, the THI broke 68 on 8 July 2022 (Figure 1). These temperatures and humidity levels were measured in the shade and would probably have been significantly lower than in the cow housing.

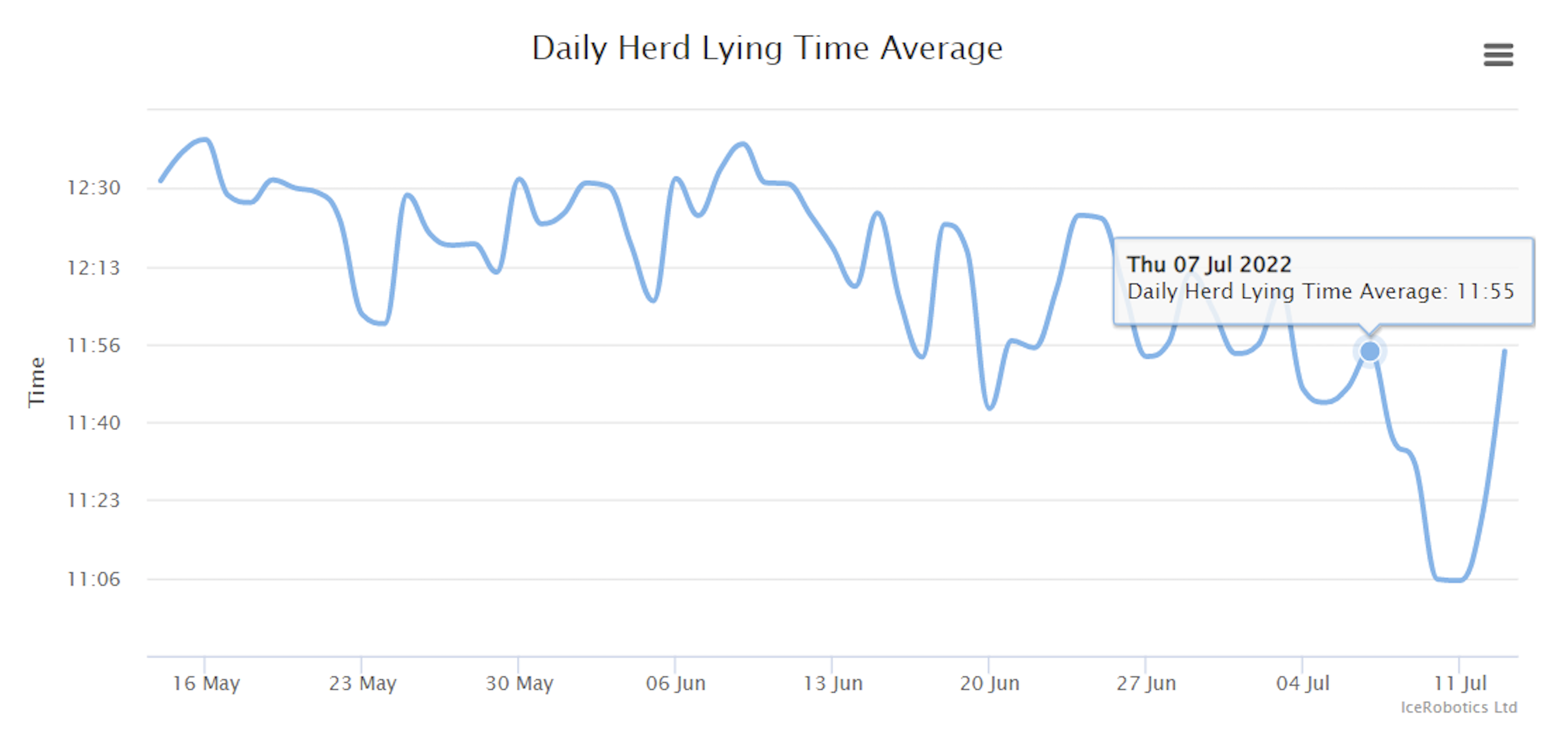

Lying times were recorded by data loggers worn by the milking herd. The mean herd lying time dropped by 30 minutes per day from 7 July, having seen a steady decline with the warmer temperatures prior to that (Figure 2).

This significant reduction would be expected to affect foot health.

On this farm (as in a number of other units), mobility scores increased in September and October. Treatment records demonstrated an increased prevalence of claw horn lesions (bruising, sole ulcers and heel ulcers).

Nick Bell

Nick Bell

Figure 1. Temperature–humidity index for the first two weeks of July 2022. The 68 threshold was crossed on 8 July 2022

Nick Bell

Nick Bell

Figure 2. Mean herd lying times (farm located South England) dropped after 7 July 2022, corresponding to the observation that THI exceeded 68 on 8 July 2022

Further information

Managing cattle and sheep in hot weather

Effects of heat stress on dairy cattle welfare