Obesity strategy restricts volume promotions in retail

Wednesday, 26 August 2020

Please note that this article was published prior to final industry consultation and some of the categories included in this analysis are no longer in scope. Readers are encouraged to check the gov.uk website for latest updates and to view IGD's summary of the promotional restrictions on HFSS products.

In store promotions play an important role in driving sales of some AHDB sector products. Policies announced as part of the new Obesity Strategy will restrict the types of promotions that can be used for products deemed to be high in fat, salt or sugar (HFSS). Below, we look at which products will be affected and what the impact may be.

Obesity strategy launch

The Obesity Strategy for England, launched in July of this year, marks a new step of intervention in England’s dietary habits, describing COVID-19 as a wake-up call and citing evidence that overweight people who contract COVID-19 face worse health outcomes. The announced policies include requirements for calorie labelling in restaurants, further restrictions on food adverts shown before 9pm, a ban on volume-driving promotions for HFSS products, and restrictions on their location in store. Public health is a devolved issue but Scottish and Welsh governments have proposed similar measures.

What is a HFSS food?

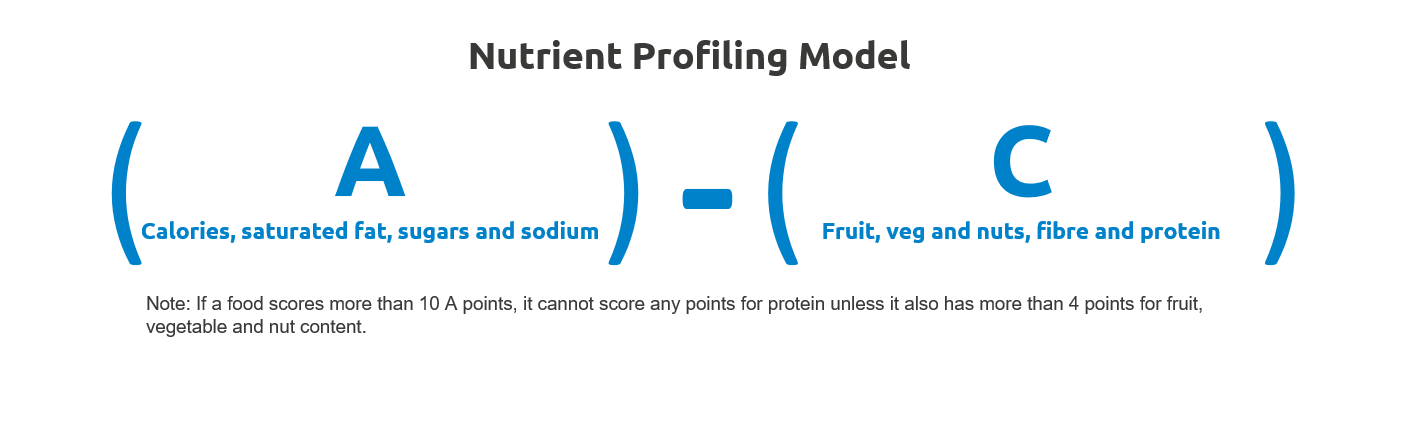

Food that is high in fat, sugar or salt (HFSS) is determined by a Nutrient Profiling Model developed by the Food Standards Agency. Foods are given a score according to their nutrient content, with points added for calories, saturated fats, sugars and sodium (A nutrients) and deducted for fruit, vegetable and nut content, fibre and protein (C nutrients). Foods scoring 4 or more points are classified as ‘less healthy’ and are currently subject to controls on TV advertising to children.

The nutrient profile is always calculated per 100g of product, even if it is usually consumed in smaller quantities. Drinks are scored in the same way, although they are deemed less healthy if they have a score of 1 or above.

Volume promotions

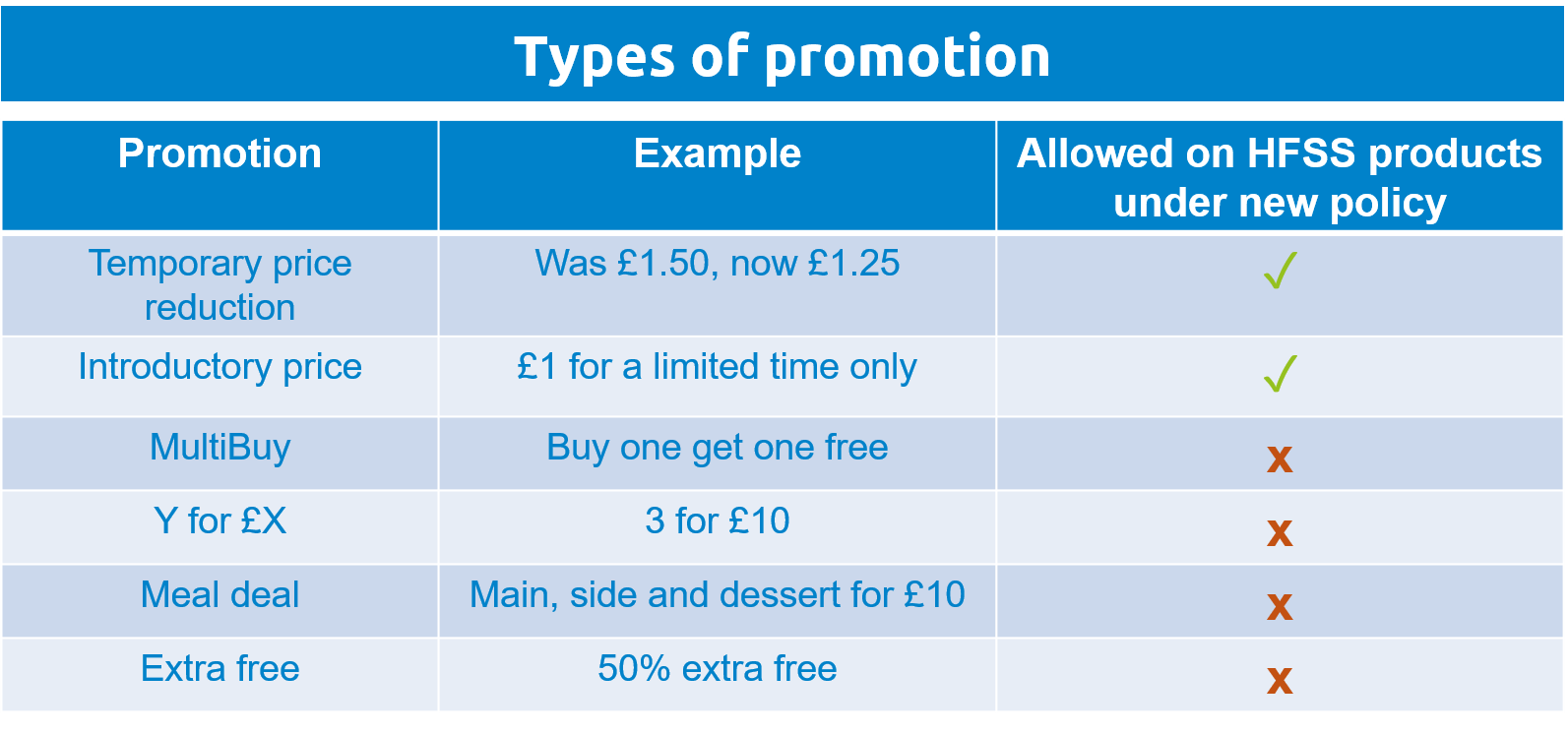

In its policy consultation document, the Government cites evidence that promotions increase the amount of food and drink people buy by around 20% and that multi-buy or volume promotions cause a greater sales uplift than other mechanisms such as temporary price reductions. They also point out that, when consumers stockpile promoted foods to take advantage of a lower price, they tend to increase their consumption, contributing to our ever-growing waistlines.

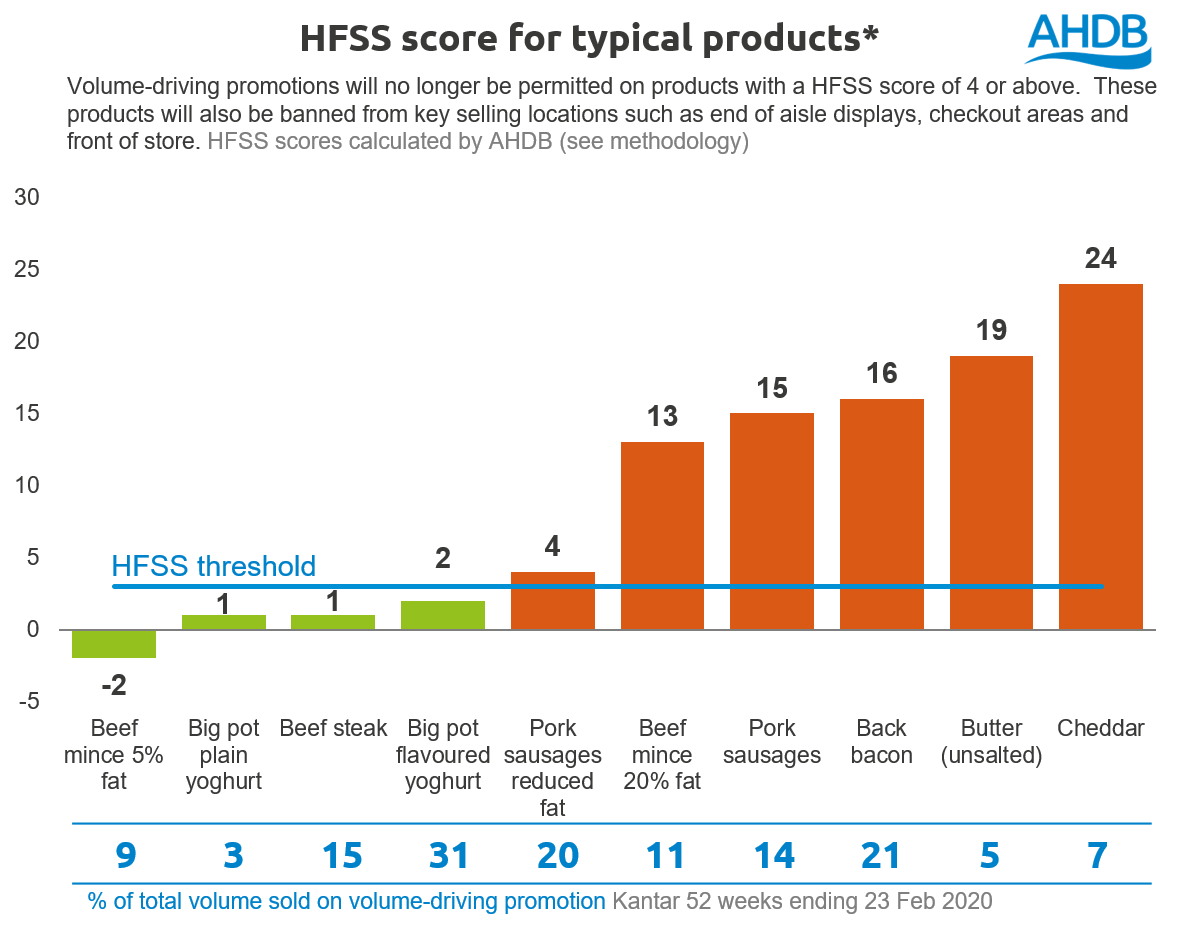

Volume promotions are important mechanisms for a number of AHDB sector products which would be deemed ‘less healthy’, according to the nutrient profiling model (see below). There is also some evidence that they help to stimulate increased consumption, particularly in perishable categories (Hawkes, 2009).

Of all back bacon sales in the year to 23 Feb 2020, 21% of volumes were sold on a volume promotion (Kantar). Bacon receives a HFSS score of 16, far exceeding the limit set for this type of promotion.

Standard beef mince and pork sausages both exceed the HFSS limit but low fat versions are much closer to the threshold. Reduced fat pork sausages used for this calculation exceed the limit by only 1 point and may be eligible for volume promotions with some reformulation.

In the dairy category, big pot plain and flavoured yoghurts would be eligible for volume promotions (though some flavours may contain more sugars and exceed the HFSS limit). Butter and cheese, unsurprisingly, exceed the limit by over 15 points each, with high saturated fat contents. However, a relatively small share of butter and cheese is sold on volume-driving promotions, temporary price reductions being more popular in these categories.

Where volume promotions are no longer allowed, policymakers hope that retailers will instead apply them to healthier products. Indeed, some low-fat versions of popular products will still be eligible. However, although volume promotions will be restricted for HFSS products, other promotional mechanics will be available, such as temporary price reductions. These would remove the incentive for shoppers to purchase more than they intended and may therefore lead to reduced volumes sold.

Scotland’s experience

There is precedent for this policy: Scotland’s Alcohol Act of 2010 banned multi-buy promotions on all alcoholic drinks sold in retail outlets but evaluation of its impacts shows inconclusive results.

In many cases, when multi-buy promotions were run in England and Wales, a corresponding temporary price reduction would be applied to the same product in Scotland. Therefore, a bottle of wine that was part of a 3 for £10 deal in England would cost £3.33 north of the border.

Researchers found that Scotland’s policy did not cause a significant reduction in volumes of alcohol sold. Instead, the number of products bought per trip was lower but frequency of purchase increased (Nakamura, et al., 2013). Another study by researchers at the University of Glasgow found the Alcohol Act was associated with a 2.6% reduction in off-trade alcohol sales in Scotland, driven by declines in wine and pre-mixed beverages, on which most multibuy promotions were used (Robinson, et al., 2014). In 2018, Scotland introduced further legislation that set a minimum price for per unit of alcohol.

Impact of removing volume promotions on food

Purchasing habits for food and alcoholic drinks are not directly comparable but Scotland’s experience may shed some light on how restrictions on volume promotions will impact meat and dairy products. The products most likely to be affected are those most reliant on volume promotions, though temporary price reductions are likely to replace these in many cases.

The nature of promotions has been changing for a number of years, with 2016 marking a widescale shift away from buy one get one free offers which have long been criticised for their impact on food waste and overconsumption. Everyday low pricing, championed by the discounters, has become more fashionable and the obesity strategy may help to hasten the demise of the multibuy.

Methodology

*Reference products were used to give a NPM score for typical products in each category. These were:

Cheddar – Own brand mature cheddar

Big pot plain yoghurt – Own brand natural yoghurt

Big pot flavoured yoghurt – Branded raspberry yoghurt

Butter – Own brand unsalted butter

Beef steak – Own brand rump steak

Beef mince – Own brand 20% fat and 5% fat beef mince

Pork sausages – Own brand standard tier sausages

Pork sausages reduced fat – Own brand reduced fat pork sausages

Bacon – Own brand unsmoked back bacon

Promotion data to 23 Feb is used because promotions were reduced significantly during the 2020 lockdown to help supermarkets maintain adequate supply. Promotion share of sausages is for all protein types (pork is 91% of sausage volumes). Promotion share of 20% fat beef mince is for beef mince with fat content between 14 and 19%.

References

Hawkes, C., 2009. Sales promotions and food consumption. Nutrition Reviews, 67(6), pp. 333-342.

Nakamura, R. et al., 2013. Impact on alcohol purchasing of a ban on multi‐buy promotions: a quasi‐experimental evaluation comparing Scotland with England and Wales. Addiction, 109(4), pp. 558-567.

Robinson, M. et al., 2014. Evaluating the impact of the alcohol act on off-trade alcohol sales: a natural experiment in Scotland. Addiction, Volume 109, pp. 2035-2043.